There are many very good reasons why Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight -a dramatization of how the Boston Globe broke the Massachusetts Catholic sex abuse scandal- is fast becoming 2015’s awards horse to beat. The performances are vigorous and assured, quill-sharpened by a script from Josh Singer that makes a meal out of mountains of names, dates, and organizations. It’s a film that manages to respect the intelligence of its audience while conducting shoe-leather journalism at the rat-a-tat pace of a tap routine.

One common point of praise for McCarthy has been how he does right by the Globe's “just the facts” principles by not sensationalizing their work on screen. There are no one-note heroes and villains, and the big, emotional nomination-reel speech stoked with fiery indignation is complicated by the institutional ideals Spotlight champions. A newspaper’s responsibility to provide the public with an accurate matter of record is what McCarthy valorizes, if anything. In a year where Dan Rather’s downfall is presented as the journalistic equivalent of the crucifixion, and multiple well-meaning issue pics lose their grounding to reworked facts and accessible “composites,” the restraint and historical fidelity of Spotlight are as laudable as they are invigorating.

For such a detail-oriented project, it's fitting that a small moment is among Spotlight’s most representative: shortly before the Globe's publication of their Pulitzer-winning story in early 2002, chief editor Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber) quickly circles an outlier in reporter Mike Rezendes’ (Mark Ruffalo) copy. “Another adjective,” he says, and nothing more. Such commitment to objectivity has led many to frame Spotlight in relation to 1976's All the President’s Men. Alan Pakula’s celluloid account of the Watergate scandal was an even more promptly turned around dramatization of nation-rocking offenses only brought to light by journalist willing to follow leads, check facts, and pound the pavement. In both films, what political or spiritual integrity is reclaimed for the public isn’t by virtue of moral superiority, but because reporters got their facts straight.

In the most famous shot from Pakula’s film, Washington Post writers Woodward (Robert Redford) and Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) sift through stacks of recorded White House requests from the Library of Congress, the camera rising skyward above them. It’s only now, nearly a half-hour into the film, that the first notes of David Shire’s sparely foreboding score are heard. As the camera continues to ascend, the scope of the conspiracy Woodstein (their commonly used amalgam name) has stumbled upon is suggested to the viewer, but not the two men soon to be at its center. All the President’s Men is first and foremost a sober paean to the dogged, unglamorous work Woodstein did to expose the Watergate cover-up, but it’s also one of the finest, most unnerving paranoid thrillers to emerge from a period of filmmaking plagued by mistrust for authority.

While Shire’s score and Gordon Willis’ saturated lighting contribute immeasurably to the fear that grips All the President’s Men, Pakula’s the one behind the miasma of suspicion that suffocates the film, even when the lights are on, and all you can hear is the rhythmic slide of typewriters in action. He does so by positioning the camera and utilizing deep space to contrast Woodstein’s straight-arrow ethical clarity with the twisted web of deceit they’ve walked into, one that’s larger and more warped than any they could possibly fathom.

Early in the film, as Woodstein is shaking the tree on the Watergate break-in, there’s a greater emphasis on shots that place the subject of the frame parallel with their surroundings and close to the camera. When Woodward is stuck gathering information over the phone (the monotony underlined by a procession of receivers stretching into the background), or briefing his editors on the facts he’s collected, the camera keeps Redford nicely squared against the rectangular dimensions of the Post’s office, the building’s rigid modern geometry fixed in place by support columns and square light fixtures. The methodical 6-minute zoom on Woodward as he finds the crucial link between misappropriated CRP (Committee to Re-elect the President) funds and its chairman, Maurice Stans, eventually compresses the background entirely, with Redford’s 90° turn over the course of the scene illustrating his character’s Cartesian understanding of how to connect the dots.

From the first shot of the opening hotel break-in, though, off-angle framing is used to skew our perception of Washington. Nowhere is that more apparent then during Woodward’s meetings with Deep Throat (Hal Holbrook), the reporter’s deep background (i.e. unquotable) source. The parkade in which they meet is a mirror image of the Post: truth reveals itself indirectly, and from the shadows. Woodward’s approach toward Deep Throat violates the linear borders created by the support columns and parking spaced, making the dark expanse of the parkade deeper and wider as he does so. Pulling the thread that Deep Throat offers sends Woodward deeper and deeper into a world that's bent to the point of breaking. At the height of his paranoia, Woodward walks across an empty parking lot at daybreak; the lights are on, but the camera insists on making every man, building, and monument in Washington look crooked.

Pakula’s choice of angles does as much to exaggerate Woodstein’s perspective as it serves to reinforce their feelings of distrust. Bernstein’s amiable pressuring of CRP’s bookkeeper (Oscar-nominee Jane Alexander) for information hits a wall when he asks for names, and we switch from alternating talking heads to a bug-on-the-wall view from the ceiling corner. She tells Bernstein at the start of their conversation that she thinks she’s being watched, and it’s this shot that makes you think she might be right. But oblique framing isn’t strictly the domain of conspirators. Woodward and Bernstein themselves are often framed at odds with one another, both to subtly reinforce their differences (one’s a liberal, the other a republican; one reads smoke to know the story, the other looks for the gun), and to show how they increasingly have to probe for answers in roundabout fashion.

The games the two employ to confirm information without explicit acknowledgment (“I’m gonna count to 10, alright? If there’s any reason we should hold on the story, hang-up the phone before I get to 10.”) put them on the right path, but provide shaky foundations on which to build a case. When their story publishes and is nearly undone by insufficient proof that Nixon’s Chief of Staff was aware of CRP’s practices, it’s foreshadowed by a tracking shot of Bernstein running across the office, ecstatic that he can give the story the go-ahead, but unaware that the hypotenuse he cuts across the office suggests that something’s not right. When editor Ben Bradlee (Jason Robards) hollers for the two to explain themselves the following day, we get a 45° angle shot of the full office that shows Woodward and Bernstein at their most vulnerable, and captures their full jog-of-shame into Bradlee’s office for a haranguing.

“In a conspiracy like this, you build from the outer edges and you go step by step. If you shoot too high and miss, everybody feels more secure,” Deep Throat says to Woodward during their final, most revealing meeting, which positions the two as close to complimentary as they’ve ever been. The secret All the President’s Men unravels is one that reaches all the way up to the top of Western democracy, the Library of Congress shot being our first indicator that this is a conspiracy built vertically. A later helicopter shot opens on Woodstein in a car, starting with the pair at street level, and then soaring up, up until much of D.C. is under the lens. While Woodstein’s vehicle is still in frame, the image is that of two men looking for a needle in a haystack that just keeps getting bigger. As we lose sight of them, and the shot keeps rising, the natural question to ask is, “just how high does this thing go?”

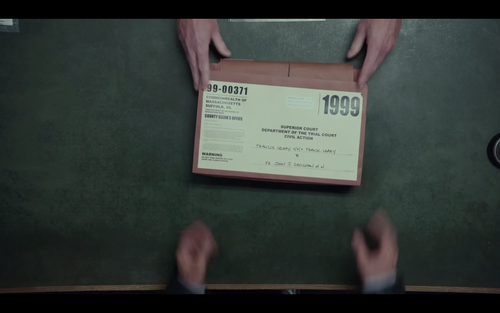

While Spotlight has a number of shots that directly evoke All the President’s Men (tight overhead framing is used to show vital sealed documents sliding across a table, just like our first glimpse of the library’s records), select comparison can present two very different takes on cinematic journalism. The extreme closeup shot which opens Pakula’s film turns the motion of a typewriter arm striking paper into an act of protest, while the naturalistic fade-up on a police officer’s backside that opens Spotlight suggests we might be watching a re-enactment out of an Errol Morris documentary. The former is sending a message, and the latter is presenting a case.

By the conclusion of each film, though, these roles have reversed: balance is eventually restored in All the President’s Men, thanks to a final shot of Woodward and Bernstein, opposite facing but parallel to each other, followed by righteously exact typewriter action printing the facts of the Watergate scandal’s fallout. Spotlight, conversely, saves what’s perhaps its most evocative image until last. Ending on the day their exposé is published, the four-person Spotlight team is in their private quarters, answering calls and gathering facts the way they have throughout the film. As Spotlight editor Walter Robinson (Michael Keaton) walks into his office at the very back of the frame, this puts Matt Carroll (Brian d'Arcy James) in the immediate foreground, and Rezendes and Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams) parallel to one another, at either side of the room and a third of the way into the frame. A film hailed for its absence of purple prose just so happens to end in a character crucifix.

Such directorial flourishes from Spotlight are fewer and further between than in All the President’s Men, and standout prominently amidst McCarthy’s otherwise buttoned-down approach to the material. But more modern journalism will inevitably be portrayed with more modern film language. When Spotlight has its game-changing Stans moment, the scene is shot in a sustained zoom out, but one that lasts maybe two minutes. Generally speaking, Spotlight is the less sedate of the two films: its score is more prominent, its moments of prolonged silence almost nonexistent, and the editing is faster and more energetic compared to a film 40 years its senior.

These stylistic distinctions, to my mind, say less about the skillsets and audiences of each director, and more about the different kinds of conspiracy each film explores. All the President’s Men looks upward to the heights of power that have corrupted a democracy’s most sacred institutions; Spotlight looks outward and into a tightly knit community tainted by not just the church’s wrong-doing, but the even more widespread confederacy of silence that allowed continued abuse of children.

Spotlight uses verticality to distinguish the workman journalists from the church officials they’re chasing and the power players protecting them. An early scene intercuts Baron walking up a stairwell to meet the paper’s publisher, who can kill the story, with Carroll travelling downstairs to collect the Globe’s past clippings on deviant priests. Eric MacLeish (Billy Crudup), the lawyer who helped sweep previous suits against the church under the rug, operates out of a skyscraper, and a montage of the Spotlight team trying to interview victims throughout Boston is dominated by the image of towering church steeples looming overtop residences. Many of the team’s early breaks in the story are presented via tracking shots of the reporters as they walk down, down further into the bowels of their own office to find pieces of the puzzle that have been buried in plain sight.

As Spotlight continues digging, and the breadth of the Church’s priest-shuffling program becomes clearer, the story begins to escape the confines of offices and archives, and spills out into the streets. When Carroll finds a familiar address in a list of priest rehabilitation homes, an unbroken take follows him as he bolts across his front porch and into the night, eventually coming face-to-face with a potential danger that’s quietly sat mere blocks away from his home. When Rezendes finally gets the sealed church documents, a damning collection of papers that prove what Boston Archbishop Law (Len Cariou) knew and when he knew it, he calls the Globe while cabbing over. McCarthy keeps Rezendes’ call uninterrupted while cutting along the cab’s path through different Boston neighborhoods, passing suburbs, churches, offices, and even established victims as the information that's been unearthed irradiates the entire city.

Whereas Pakula’s linear expressionism whips his film into a paranoid frenzy, the strong emotional catharsis Spotlight aims for demands the film be properly burdened first. Spotlight’s most surprising, and ultimately satisfying accusation is reserved for the Globe itself: 20 years earlier, Robinson unknowingly buried the very story he’s out to cover in 2001. When Robinson first hears from MacLeish that a list of victim names was sent to him years ago, he denies it, and in the moment, truly believes himself innocent of any wrongdoing.

But the scene ends out of the established pattern of reciprocated close-ups, concluding on a long shot of Robinson and Pfeiffer in the lobby of MacLeish’s office. Our diminished view of the reporters is timed to coincide with the moment they realize they may have been a part of their own story all along. It’s perhaps McCarthy’s most personal shot in the film: he and Singer's own research into the case, not the information given to them by the Globe, is what led to this narrative-altering revelation about the Globe’s mishandling of the information the first time.

Befitting a film so defined by its relationship with Catholicism, Spotlight’s understated climax is a pair of confessions, one from a knowing conspirator, and the other from an accidental accomplice. Once Robinson gets his own deep background source to admit complicit participation in the Church’s cover-up, Spotlight’s list of deviant priests has the necessary confirmation required to run in the paper (as in All the President’s Men, that confirmation is given in roundabout fashion that amounts to little more than a pointed finger and a thumbs up).

But in order for the Globe to publish the story with a clear conscience, Robinson must first offer up a confession of his own, taking responsibility in front of the editorial staff for the scoop he missed 20 years prior. The scene is shot mainly in close-up, with emphasis placed squarely on the characters as they go eye-to-eye with one another. It’s the cleansing inverse of similar shots that occur after Pfeiffer first discovers the clipping Robinson made of MacLeish’s list, midway through the film. Their secret is captured in wordless looks between the two throughout the second half of the film, an example of the ease with which a code of silence can take hold of those trying to forgot old mistakes.

The hush over Boston that Spotlight seeks to break is inextricably tied to most every aspect of life and identity in the city. Text and subtext commingle so closely that there’s often no point in looking for a distinction: survivor Joe Crowley (Michael Cyril Creighton) explicitly points out, and even chuckles when his interview with Pfeiffer occurs in a playground situated next to a church. The story’s publication date, which coincided with the day of the Epiphany, is of mild amusement to Carroll, Rezendes, and the audience. McCarthy's film uses smaller poetic touches -opening and closing the film close to Christmas, intercutting between two wildly different but related victim accounts, loading the mis en scene with Sox regalia- to interconnect most every aspect of his story, not make those touches the story itself.

This is why a shot as potentially loaded as Spotlight’s finale doesn’t play like a capital-S load of symbolic hooey. The arrangement of the Spotlight team can be viewed as indicative of Robinson's salvation, an affirmation of the value the team's “good work” have had on the world, or simply as an accidental staging quirk. You can read whatever you want between the lines of dialogue and the planes of action, but the story that really matters here is the one that wound up on the front page of homes across Boston on January 6th.

Once Robinson’s final testimony is on record, Baron wraps things up with, what is by his standards, a moving speech. “You have all done…very good reporting,” he says, Schreiber still underplaying each line like a bearded Sphinx. Baron’s unflappable pursuit of objective fact makes him an almost impossibly idealistic embodiment of journalism as it’s best been practiced, and how we hope it always will be. Just as All the President’s Men is Redford walking through that parking lot, Spotlight is Baron removing an adjective from the story so that the truth can speak for itself. But also like All the President’s Men, Spotlight is that last long shot of Baron, way, way in the back of frame, just sitting at his desk, another journalist willing to work from the outer edges inward, step by step.