This post discusses plot details up to this week's Season 3 finale.

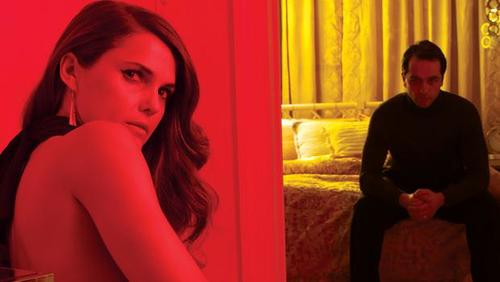

Through to the end of its recently concluded third season, FX’s The Americans –a series about deep cover K.G.B. agents posing as a married couple in ‘80s D.C.- lived up to every high expectation I’ve hoisted on it since calling it my favourite show of 2014. I’ve hit a point of semantic satiation when throwing out superlatives like “suspenseful,” “smart,” “heartbreaking,” and “the best show on TV.” By now, praising The Americans just feels like yelling into an echo chamber occupied by fellow TV critics, and a pitifully small home-viewing audience.

Writing about the show week-to-week made the dense contours of each episodic tree much easier to grapple with than the season’s Siberian taiga as a whole. Season 3 was, by design, a more open-ended year of The Americans, one uninterested in providing the same degree of closure found in the tightly wound season that preceded it. A recent interview with one of the show’s newest writers, Tracey Scott Wilson, helped bring one particular element of the season as a whole into focus for me. Speaking with Observer.com, Wilson said:

“We have to really devise ways to externalize the internal…Especially with Elizabeth, because she’s a character who’s not intentionally outwardly emotional. She doesn’t open up to many people so just finding ways to show how she feels without her overtly saying how she feels is a challenge we always have.”

The Americans, as a rule, rarely uses dialogue to reveal a character’s psychological state. This puts far more responsibility on the performers and production team to deliver the emotional context of a scene, but that’s a big reason why the show is so rewarding to watch. But given how intensely complicated that emotional context can get –characters often adopt different personalities or identities depending on who they’re with-, I sympathize with Wilson’s struggle to maintain a “show, don’t tell” philosophy when your main characters do nothing butshow misleading sides of themselves.

As a result, one of the show’s most laudable, challenging elements is one of its most subtle: a complete rewriting of the sexual politics of spycraft. On the surface, it can appear as though The Americans has simply flipped the basic gender expectations of its two lead characters, with Philip Jennings being the sensitive, self-doubting father, and Elizabeth being the stoic, cold-blooded zealot of Mother Russia. Elizabeth’s proven knack for beating the crap out of people also checks off the physical component of what can today pass for a “Strong Female Character,” a phrase that usually puts too much emphasis on the first word, and not enough on the last.

The Americans established this central dynamic between its two leads from the very first episode, and built on it with nuance. At the time, my only major concern about the show’s future after the outstanding pilot was the choice to make Elizabeth a sexual assault survivor. It’s a very tricky backstory to give a lead female character, one that often threatens to completely define her role on the show, or be used as an excuse for her to take on more traditionally masculine traits (“she got tough because she was traumatized,” goes the lazy rationale). The Americans wisely integrated this detail into Elizabeth’s greater individual identity, the first season weighing her betrayal by a superior officer against her dogmatic devotion to her country, and the second letting her rework the experience into a convincing cover identity as a victim in need of help.

For Philip, the violence required to complete missions is what drove him deeper and deeper into self-loathing through the first two seasons, but that changed in the third. In order to infiltrate the home of a high-ranking C.I.A. official, Philip had to physically and emotionally seduce Kimberly, a 15-year-old girl with an exploitable interest in older men. Though never comfortable enough to outright say what needed to be done, Elizabeth, and the Jennings’ new handler, Gabriel, both believed that the terrible situation was in service of a greater good. Philip’s constant evasion of Kimberly’s advances became a sticky wicket for those he worked with, who viewed his predicament with the moral calculus afforded to bystanders: how many lives will you sacrifice just because you don’t want to sleep with a 15-year-old?

As a man, Philip’s willingness to have sex is taken as a given, an assumption reinforced by typical espionage tropes. In one of the season’s most harrowing sequences, flashbacks show that Philip was trained to have sex with all different types of people. At first, this means sleeping with a beautiful young woman, essentially the only type of female character of use to most spy fiction. James Bond hinting at maybe, possibly, perhaps having a homosexual affair at one time in 2012’s Skyfall, or subtext in le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, is often as outside the heteronormative comfort zone as this stuff usually gets. But then we see Philip sleeping with a much older women, and then a man, all as a means of ensuring he will be able to convincingly pass for whatever orientation his mission requires.

Beyond just the physical toll being a sexual Swiss Army knife entails, Philip’s emotional involvement with long-standing assets provided a throughline for all of Season 3. The premiere featured the murder of Annelise, a naïve but harmless woman Philip had been entangled with sexually for years, and whose death owed heavily to Philip’s involvement. The back half of the season required Philip to compromise his cover and conscience even further to protect Martha, the woman who shared not just her bed, but her life with “Clarke.” In essence, Philip was forced into a position traditionally reserved for women in spy stories: a one-size-fits-all outlet for the sexual desires of mission targets, whose greatest weakness was growing attached to the person they’re meant to seduce.

We never learn if Elizabeth had to go through similar training -it’s just taken as a given that she can deal with unwanted, or unfulfilling sex, because that’s a reality for many women anyway (in Season 2, the Jennings’ female handler recruits a 17-year-old boy much the same way Philip is meant to recruit Kimberly). For Elizabeth, the greatest sexual revelation for her this season also cuts against the grain of average genre expectations. When sleeping with a target for the first time in more than a year, Elizabeth is stunned, then shamed by her enjoyment of the encounter. In part, it’s because the mark shows heretofore-unseen interest in ensuring Elizabeth’s satisfaction, going down on her before they have sex. But because she considers herself a professional, and is trying to maintain as honest a relationship with Philip as possible, she’s made to feel as though she’s failed both herself, and the integrity of her marriage.

That shame leads her to fellating Philip the same night as a means of apology, something he never asked for, but is, again, assumed to want. In the process, Philip is reminded of Annelise going down on him during the premiere, which he didn’t solicit either, but like Elizabeth, felt guilt for enjoying anyway. Oral sex became a blunt instrument for The Americans in Season 3, used as an act of submission or seduction from giver to receiver. By ignoring intimacy and communication in favor of simply getting your partner off, it makes sex a transaction instead of a source of meaningful connection, which is at the heart of the dissolving relationship between Philip and Elizabeth by season’s end.

Not coincidentally, Philip and Elizabeth’s marriage is at its most stable at the start of Season 2, when the two are seen reciprocating oral sex at the same time. Since then, though, their individual and shared sex lives have been challenged by the sides of themselves they can’t, or won’t share with one another. Season 3 ends with Philip going to an EST seminar that presents personal identity as being expressive of sexual identity, where taking ownership of one’s life means taking ownership of their body and desires. The only way he’ll be able to do either, though, is by reclaiming his life from his nation. Yet doing so would betray Elizabeth, the woman he needs to make his life, and family whole. The ability to externalize these internal needs to Elizabeth is ultimately what stands as Philip’s greatest challenge going forward.

For Elizabeth, though, the path isn’t so clear. “She’s no less passionate but she’s feeling things that she maybe wouldn’t let herself feel before,” Wilson says of Elizabeth’s journey through Season 3. Those feelings include the aforementioned sexual encounter,unexpected empathy for a woman she has to kill, and the emotional strain of her mother’s approaching death. The final shot of the season, of an Elizabeth galvanized and distanced from Philip by Ronald Reagan’s “Evil Empire” speech, suggests those new feelings, along with Philip’s own, will be next year’s most likely casualties.

The Americans has subtly maintained itself as one of the best feminist dramas on TV, more through action than overt statement. When looking back on the best moments of the season, all include, or are dominated by women, whether it’s Philip and Elizabeth revealing the truth about themselves to daughter Paige, or the powerful reunion between three generations of women we get in the finale. The Americans wasn’t great and different this year simply for having “Strong Female Characters” or “Vulnerable Male Characters,” but because it made it that much harder to even try to box these characters into categories that simple.