Happy New Year's Eve everybody, let tonight's celebrations be merry, and your holiday hangovers brief. Last update for the year, with final 2012 episodes from both Arrow and Parks and Recreation. But as a special year end send-off, I also threw together a Top 20 TV shows of 2012 article for Wegotthiscovered last week, part 1 of which can be found here. Part 2, which has the Top 10, as well as a video top 10 I cooked up, is right here. The video portion was a real learning experience, in that I learned when I do a Top 10 list, my writing patterns ape Alan Sepinwall, but my voice sounds like Dan Fineberg, two very fine TV critics I hope to learn more from in 2013. 2012's been another fruitful year of this little experiment, one that I assure you will only be getting weirder, more refined, and more refined in its weirdness, next year. Thanks for reading, and happy New Year!

Chimes Past Midnight: The Evolving Legacy of Orson Welles

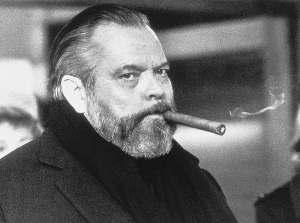

“How much obligation do you feel to a mass audience?” The question comes from a woman in a packed lecture hall, indistinguishable amongst the eager crowd of onlookers. She’s speaking to Orson Welles, and the year is 1981. Welles, now in the latter half of his 60’s, with a full beard and white hair peppered by a few streaks of black, chews over the question for a moment, and looks a tad disgruntled by the thought before replying. “I would love to have a mass audience,” he lobs back, convinced he’s got a winner, “you’re looking at a man who’s been searching for a mass audience...and if I had one I’d be obliged.” He’s right, and the audience laughs along with him before breaking out in applause. It’s a typical late-life Welles witticism, disarming and self-deprecating, while maintaining a cool undercurrent of tired frustration. He was speaking to a group of film students at the University of Southern California after a screening of his 1962 film The Trial, which Welles himself considered the best he ever made. Fittingly, the comment wouldn’t be heard by much of an audience, the clip itself released, not in his planned behind-the-scenes picture, Filming the Trial, but as part of Orson Welles: The One Man Band. The film is a mix of archival and unseen footage about Welles, and was released to little fanfare in 1995. It was assembled by his wife Oja Kodar, as a means of commemorating the tenth anniversary of his death.

More fitting is the content of the film itself: though partly a primer on Welles’ many unfinished projects, One Man Band is more interested in the man than his craft, so far as the two can be separated. It opens with Welles striding onto a stage, and he’s joined by a few stagehands before producing a duck from an empty barrel, as though it were his own special way of saying “hello”. When we return to that university building filled with prospective young filmmakers, the questions focus mainly on personal insights as opposed to industry ones. The film closes with a combination of Welles’ most popular sign-offs, fading into black while reminding you that, “this is Orson Welles, remaining, as always, obediently yours.”

It’s an appropriate goodbye, both for his wife and the viewer at home, as the further we get from Welles' death, the more his presence is missed. While the relative merits of the Welles canon will be the subject of fierce debate for generations to come, the public’s impression of Welles continues to evolve in the aftermath of his passing. Ask one person and you’ll hear about the child prodigy who conquered every medium he applied himself to, only to be sabotaged by studio jealousy and backstabbing. Ask another, and the image of a controlling, gluttonous fraud will be almost impossible to erase from your mind, given the number of such accounts.

He’s an inescapably contrarian figure, all the more so thanks to how little he disguised his ability to be the villain, something friend Peter Bogdanovich knew when telling Welles “no one ever wants to play [Brutus] – but you[1].” It’s a challenge to try and understand a man who “was not his own record keeper; he preferred the myth and fun of making up stories[2],” to quote David Thomson, one of many biographers who has tried to piece together a stabile truth about Welles through all the hearsay. Thomson is in common company among those who, in the decades after Welles’ death, have attempted to pin down what ought to be our final opinion of the man. But only a persona as incendiary as Welles' could make that task such an ongoing affair.

By the time of his twilight years, it seemed the cultural consensus of Welles had already been reached. His increasingly erratic production schedule as director saw only five films completed between 1960 and 1985, two of which were documentaries, and one a made-for-TV movie. In between those completed works were a litany of unfinished passion projects, including a Don Quixote adaptation started with decade’s old footage, and the semi-autobiographical The Other Side of the Wind, which filmed in fits and starts. Supporting these myriad ventures meant assembling funds by any means necessary; Welles had been all but blacklisted among studios over the course of his early years in Hollywood, and his less than triumphant return to American cinema with 1958’s Touch of Evil established his status as box office poison.

Sometimes cashing a cheque meant borrowing hundreds of thousands of dollars from industry pals, of which repayment was often uncertain, or making guest appearances in films of varying note. Other, more infamous ventures involved getting into bed with any and every product that wanted to profit off of Welles’ distinctive voice and domineering figure. Though these were simple jobs meant to pay the bills, his inability to finish any actual projects made these the appearances of “a famous public figure, an inescapable monument for himself,[3]” to quote Thomson; where once was an artist, now sat a washed-up movie star, cashing in as a grocery aisle pitchman. Findus frozen peas and Paul Masson wine remain two of his more memorable patrons, mostly thanks to widely disseminated footage of Welles squabbling backstage with the director, or drunken bloopers, the scandals over which largely eclipsed the ads themselves. All this, combined with Welles’ comic girth, made his winter years the subject of frequent lampooning.

Of all the imitators, John Candy's impression of Welles on SCTV bares the most striking physical resemblance to the Welles of that period, seen practicing a holiday tribute ad with Liberace, only to flub his lines and berate the staff before making off with a turkey. He’d revive the character for the short-lived Billy Crystal Comedy Hour, this time playing on Welles’ penchant for magic by giving Crystal ridiculous requests in an effort to divine a number, only to lose interest -before the trick's payoff-, at the promise of food backstage. The latter bit was filmed in 1982, suggesting that Welles’ appetite, love of magic, and prima donna working antics were his most publicly identifiable traits. A decade after his death, the roasting continued largely unabated, but now in a medium that harkened back to his days as a New York theatre savant. Newspaper caricatures were among the earliest means of bringing Welles to an audience that didn’t frequent Broadway, and his post-mortem media revival would start with a pair of cartoons.

When trying to find the proper cadence for a rat with an oversized head and plans for world domination, voice actor Maurice LaMarche instantly thought of Welles, and the megalomaniacal lab rat called The Brain was born, bringing Orson’s signature voice to a new, much younger generation in The Animaniacs. Adult viewers would also see an animated recreation of Welles on The Critic, a primetime cartoon based on parodies of famous films and actors. Welles’ potential as comic fodder was still fertile territory, with appearances taking shots at his advertising gigs (“I don’t need to do this, I’ve got a fish stick commercial in an hour!”), as well as his size and love for tricks (“I will make this jug of wine disappear”). He'd fair no better outside the world of cartoons. When reproduced in a more mythic fashion for a cameo in 1994’s Ed Wood, the aura of greatness implied by his appearance is tainted by the fact that it’s the world’s most notoriously awful director who looks upon him with such reverence. Bringing back Welles, whether in animated form or in the flesh, was just the setup for a punch line.

Littered throughout all the call-backs to Welles’ troubled final years (Pinky and the Brain recreated Welles’ ignominious rant over a frozen pea commercial nearly verbatim) were references to his actual work, particularly, Citizen Kane. The low-angle podium shot has been replicated ad nauseum, and any close-up of a mouth uttering two syllables is almost assuredly a nod to Rosebud. Much of the awareness of Welles in the years after his death came from parody of Kane, often affectionate (The Simpsons has all but remade the film via references), in one way or another (there was, in fact, a pornographic parody, Citizen Shane, made in 1996). The public may have remembered the man behind The Greatest American Film of All Time as a sell-out and a drunkard, but at least his tarnished reputation had done little to upset Kane’s destined longevity.

What better way then, to re-stoke the gossip and controversy of Welles, than by attacking the golden production which made him a legend, one founded on ambition, ego and a media battle the likes of which only old Hollywood could have pulled off. 1996 saw the drama behind America’s greatest drama revived in The Battle Over Citizen Kane, a PBS documentary that pit the young Welles in a fight to the finish with newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst over the fate of the film. There’s an inherent romanticism to the Kane’s production, described by Paul Arthur in a 2000 edition of Cineaste, where Welles and Kane are “positioned not as distant patriarchal icons of a vanished system but as representative of vibrant artistic struggles against crusty conventions of style and narration.[4]”

That story is largely ignored in the film, which deals more with the reclusive media magnate Hearst, whose use as inspiration for Kane has been well-documented. The documentary goes further to imply that the fighting between Welles and Hearst was merely a passing of the baton, from one generation’s great success-turned-failure to another. Welles is made out to be a brash upstart who made a name for himself fighting Goliath, only to fade into obscurity on the heels of victory. His subsequent works are largely glossed over in the wake of Kane, and the film aims to make tragedy out of an imagined status as a one-hit wonder.

The story would get a dramatization a few years later in RKO 281 (1999), an HBO TV movie that casts similar aspersions on Welles the way the documentary did, but in a grandiose fashion he surely would have admired. The backdoor chicanery of Hearst (James Cromwell) and the conspiratorial meetings of studio heads looking to sabotage Kane have all the cloak and dagger manoeuvring Welles believed had haunted him through his career, while his abuse of scripter Herman “Mank” Mankiewicz (John Malkovich) is portrayed as a betrayal of his own. The same goes for RKO studio head George Schaefer (Roy Scheider), who gets drawn into protecting Kane because of his admiration for Orson, only to lose his job in the process of saving the film. Besides showing Welles' abandonment of those responsible for his initial success, the film, like The Battle Over Citizen Kane, finds other ways to draw strong parallels between Welles and Hearst in “a parable focused on outsized, ill-matched power addicts.” It’s no more apparent than in an invented warning from Hearst to Welles, telling him that “my battle with the world is almost over. Yours, I’m afraid, has just begun.”

It’s insertions like these that, while not quite revisionist, started a trend in Welles fiction, wherein the filmmakers would try and explain the methodology behind Welles’ process, or even try their hand at psychologically probing a ghost. RKO 281 points directly at Mrs. Welles as inspiring the man’s indomitable drive, telling a young Orson, “you were made for the light,” and that “one chance” is all we get in life. It also marks the start of elaborate reference dropping to other works in the Welles canon, in a bid to acknowledge his works beyond Kane, if only in passing. The deathbed-ridden Mrs. Welles looks both like Kane and Mrs. Amberson at the end of their lives, though the tone of her words when giving parting advice to a young Orson gives the impression their relationship had more in common with the Bates family than the Ambersons.

The references themselves were often more complex or subtle than simply reproducing Kane’s most memorable shots. Sometimes the call-outs were used as a means of giving imaginary origins to other Welles works, with throw-away phrases and images made to give the impression that inspiration followed the man wherever he went. Other examples are completely superfluous, like recreating the iconic stairway shot from The Magnificent Ambersons using Hearst and Marion Davies, despite Welles’ not being in the scene. They’re showy and add little beyond letting the filmmaker give a sly wink to the audience that recognizes the homage, but that they exist in the first place hints at appreciation for Welles that extends beyond just Kane.

Less than a month later, Welles was once again in actual theatres for Tim Robbins’ Cradle Will Rock, though this time he was anything but the star. Rather, Welles’ struggle to make Marc Blitzstein’s pro-union musical under the Federal Theatre Project is only one piece of a period labour drama featuring a cast of dozens. It features a young Welles (Angus Macfayden), already a theatre company director at 22, and it’s the most light-hearted portrayal of the man that doesn’t resort to outright mockery. Welles’ famously bitter relationship with John Houseman is used as the basis for good-natured sparring, as their clashes over art and pragmatism provide plenty of comic relief.

Welles is shown as more of a combative artist than a control freak, suggesting that his early days in the theatre lacked the extreme authority issues he was later known for. Likely this was due to the film’s altogether rosy look back at a time of immense political turmoil, but it does posit there was a time when Welles needn’t be the centre of attention to be a part of something great. Maybe he enjoyed being a part of the company’s triumphant first performance despite fear of being cut-off from the theatre community and government funding. Or perhaps, as Thomson believes, Welles was “as romantic and as moved by the demonstration of defiance” as everyone else, but this was just his first taste of the “rush of joy and applause that is only provoked by outrage.[5]”

Focussing on ads, the theatre, and Hollywood leaves the majority of Welles’ actual life and work in the cinema untouched; 281 and Battle lead us to believe that he peaked at 25, glossing over the decades-long struggle Welles faced working in Europe. It’s when his story leaves the glamour of Hollywood and the energy of the New York theatre scene that the real weight of being the industry’s persona non grata comes out, something captured by Vincent D’Onofrio in his 2005 short film, Five Minutes Mr. Welles. Expanding on the interpretation seen briefly in Ed Wood, D’Onofrio’s Welles is in the throes of a professional nadir, trying (and failing) to remember lines for his role as Harry Lime in Carol Reed’s The Third Man. It’s the most unflattering portrayal of Welles out there, keeping him confined to his room, like K in The Trial, in order to heighten the sense of dread and paranoia.

Welles is convinced he’s being watched and spied on, which is actually proven true when assistant Katharine (Janine Theriault) admits she’s been keeping tabs on him for studio higher-ups. Despite showing him as a drinker, womanizer and a clumsy line-reader, there is sympathy to this version, as we get to see how quickly nerves can fray when the world wants you to see you shine almost as badly as it wants to see you explode. Less than ten years after Kane, who wouldn’t believe Welles’ success had more to do with chance than genius? The film settles somewhere in between, as it climaxes in Welles coming up with might be his greatest piece of writing, the cuckoo clock speech. Some would call it the definitive Orson Welles moment, where little details accrued from living over-dramatically at all times synthesize at the last minute out of sheer desperation and a little dumb luck. It would seem that Welles the genius and Welles the fraud were no longer mutually exclusive identities.

2009 brought what could be considered the most layered interpretation of the developing Welles discourse, in Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles, a fictionalized account of the days leading up to the Mercury Theatre Company’s first performance, Caesar. Christian McKay, though looking far too old for a 21 year-old, does better than any of his contemporaries at showing the wild energy and fierce loyalty the young Welles could inspire in people, as well as the fear that came with ever crossing him. He’s a destructive whirligig of ideas and demands, brazen in his manipulation and bullying, particularity evidenced in his often hostile relationship with John Houseman (Eddie Marsan). It’s from a time when he could still get away with virtuoso acts like rewriting a radio play mid-broadcast, as his star was still rising. This was Welles in his prime, a man “driven by a relentless demon,” one that must have been personal and all his own, as Warren Kliewer noted that “his vision of the director as seminal artist and of direction as an art form of its own terms has inspired countless imitations...most lacking Welles’s genius.[6]”

Linklater himself admits the film is far from a biography, and that, as he told the New York Times, “you can see whatever you want there. You can see all the genius, or you can see future tragedy.[7]” Both are present, even in the same moment, no more so than as Welles watches the curtain rise on Caesar’s premiere, noting that “this is the night that either makes me, or fordoes me.” It’s an ironic proclamation, as launching into the artistic stratosphere off of Caesar is what inevitably dooms him; the maverick techniques and furious passion that wows his theatre audience is the same kind that would make him an exile for most his career. Linklater’s Welles is an electric, unstoppable force, unburdened by studio meddling or professional vendettas, and watching McKay is almost like seeing the legendary wonder-boy reborn for a new millennia. We see in Me and Orson Welles the return to his heyday, when it looked like anything and everything was within his reach.

So why then, did it take so long after his death for the world to look back at Welles as anything other than a has-been or a charlatan? Perhaps a new generation, one that could take the long view on Welles’ life instead of just its fading years, would be better able to appreciate what he did accomplish instead of what he didn’t. The proliferation of his work through increased media availability almost certainly aided in bringing more than just Citizen Kane to developing Wellsians, and it didn’t hurt that much of the old guard that harboured some opinion of the man passed along with him in the years since 1985. With the book finally closed on his life, the questions of “what’s next,” and “what horrible thing has he done now,” no longer exist, and the expectations are finally gone.

We can finally view the life of Orson Welles as a whole, and the greatest take away, I believe, is that his was a voice, a passion and a zest for life that is sorely missed. Maybe poking fun of him in cartoons and portraying him as a talentless monster was the best way to reconcile the years after his death with the final years that almost undid his legacy. But the longer the world goes without Orson Welles in it, the more his absence is mourned. It doesn’t matter whether you thought he was a genius, a thief, a bon vivant or a boor, because if he was any or all of these things, at least that brilliant, irascible madman was, as he liked to say, obediently ours. Perhaps he secretly did have a mass audience all these years, as more and more, it seems like, in his own way, he was always obliged to us.

References

1: Welles, Orson, Peter Bogdanovich, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. This Is Orson Welles. New York: Da Capo, 1998. Print.

2,3,5: Thomson, David. Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles. New York: Vintage, 1997. Print.

4: Arthur, Paul. "Reviving Orson: Or Rosebud, Dead or Alive." Cineaste 25.3 (2000). Print.

6: Wilmeth, Don B., and C. W. E. Bigsby. The Cambridge History of American Theatre.Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999. Print.

7: Lim, Dennis. "Citizen Welles as Myth in the Making." The New York Times. 20 Nov. 2009. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/22/movies/22welles.html?_r=1>.

Top 8 Political Comedies

Originally Posted on August 8th, 2012, at Playeraffinity.com

It's an election year, which means the time has come to devote a great deal of thought and energy into analyzing the foundations of democracy, with roughly 2 percent of said discussion actually being serious or thoughtful. You don't have to be the DJ3000 to realize that when it comes to politics, sometimes you gotta laugh to keep from crying, especially at a time when the values we should be celebrating get buried in the fracas of a 24-hour news cycle, that highlights gaffs and attack ads instead of platforms.

But that's all good news for the estate of comedy, as some of the best films out there revel in taking the piss out of the democratic process. Whether lampooning government at the district level, like this week's The Campaign, or targeting the national halls of power, this list of political spoofs and send-ups is guaranteed to make you laugh at how eerily accurate the satire is… then sigh dejectedly at how eerily accurate the satire is.

8) Idiocracy

Mike Judge's barely released cult favorite takes the feeling of being the smartest guy in the room and runs with it to a horrifying extreme, when a cryogenically frozen army schmoe awakens in 2505 to find that proliferation of stupidity has decimated the world's collective IQ. In a world where the language is a sub-Xbox Live mix of grunting and sexual pejoratives, and the biggest TV show is called "Ow! My Balls!", it's easy to overlook Judge's gentle commentary on growing anti-intellectualism and corporate ownership, even if evolving Starbucks into a futuristic sex parlor seems less satirical every time someone mentions the chain by name.

Cynical Soundbite: "You think Einstein walked around thinking everyone was a bunch of dumb shits? Now you know why he built that bomb."

7) Election

Is it possible to take the electoral process seriously when your introduction to it is so utterly pointless? The candidates running for class president in Alexander Payne's Election are a cross section of the exact sorts of schemers and idiots that dominate the political landscape more than seems likely. There's the insanely driven overachiever willing to do anything to get ahead, a popular golden boy who's dumber than a sack of hammers, and a fringe candidate who inspires voters by telling them not to vote. When dastardly plots are made and lives are ruined for the sake of one meaningless election, imagine the kind of damage a real one could do.

Cynical Soundbite: "We all know it doesn't matter who gets elected president of Carver. Do you really think it's going to change anything around here? Make one single person smarter or happier or nicer? The only person it does matter to is the one who gets elected."

6) Thank You for Smoking

Dealing more with the importance of spin in politics than the process itself, Jason Reitman's directorial debut is a gleefully transgressive love letter to the most indefensible groups out there: giant corporations and the lobbyists embodying them. Led by Aaron Eckhart as Nick Naylor, the self-described Colonel Sanders of nicotine, Thank You For Smoking lays waste to all players in the game of media control, from Hollywood and advertisers, to crusading elected officials. It takes the stance of a magnetic know-it-all that knows how to thumb its nose at the system it's exploiting, and look damn good doing it. Although there's a sweetness beneath all the self-interested rationalizing, rarely does such dark wit come in package so slick and entertaining.

Cynical Soundbite: "I get paid to talk. I don't have an MD or law degree. I have a baccalaureate in kicking ass and taking names. You know that guy who can pick up any girl? I'm him. On crack."

5) Duck Soup

The kind of farce that only the Marx Brothers could have mustered, Duck Soup launches of a war of words and vaudevillian buffoonery, before starting a real one between bankrupt Freedonia and conniving neighbor state Sylvania. Groucho leads as Freedonian despot Rufus T. Firefly, who's too busy playing the court jester to bother with anything that resembles good governing. Despite Groucho's own admission that the film was intended to evoke laughter instead of discourse, Duck Soup has garnered increasing respect for its take on fascism in WWII-era Europe, the feather in its cap being an outright ban from viewing in Mussolini's Italy.

Cynical Soundbite: "I wanted to get a writ of habeas corpus but I should have gotten a-rid of you instead."

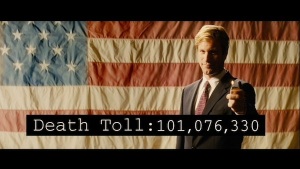

4) Wag the Dog

This pitch black satire scores points for its astounding prescience, telling the tale of a political propaganda expert who starts a phoney war with Albania to distract the public from a presidential sex scandal. Its release in late 1997 was barely a month prior to Bill Clinton ordering bombings on terrorist bases in Afghanistan, which came just three days after Clinton confessed that he was the one who had dealt that which had been spelt on an item in Monica Lewinsky's wardrobe. Immaculate timing aside, Wag the Dog features Robert De Niro and Dustin Hoffman in top form, each playing one half of the increasingly incestuous relationship shared by the government and Hollywood.

Cynical Soundbite: "The war of the future is nuclear terrorism. It is and it will be against a small group of dissidents who, unbeknownst, perhaps, to their own governments, have blah blah blah. And to go to that war, you've got to be prepared. You have to be alert, and the public has to be alert."

3) The Great Dictator

A "prince and pauper" story that trades the street urchin for a forgetful tramp, and royalty for a snivelling tyrant, Charlie Chaplin's first talkie is considered a standout even in a career as illustrious as his. With the duel role as both an amnesiac Jewish barber and the gibberish spouting dictator Hynkel, Chaplin's thinly veiled mockery of life in Nazi Germany starts off like your typical silent-era slapstick, but quickly ramps up to be an audacious condemnation of fascist Europe, much of which was written before the outbreak of World War II. As if more aware than most of the future horrors the Nazi party would unleash upon the world, Chaplin ends the film using the advent of talking pictures to its fullest potential, delivering one of the greatest and most moving speeches ever recorded on film.

Cynical Soundbite: Just watch the speech. It'll pretty much wipe out whatever cynicism you're feeling.

2) In The Loop

Certainly among the foulest comedies of the last decade, and perhaps the best full stop, In the Loop is a head-spinner of rapid-fire threats and miscommunication between British and American officials, in which a decision to go to war is as much about what isn't said, as what is. For as furiously as the characters will throw out political acronyms and intricate insults, simple human stupidity, greed and vanity are the real forces driving a political machine that keeps those ostensibly running it either a few steps behind, or in danger of being chewed up underfoot should they get in the way. With a ferociously funny script that recalls Oscar Wilde after a bachelor party with the guys from South Park, never has the quagmire of modern politics been so dense, yet relatable at the same time.

Cynical Soundbite: "Okay. Firstly, don't raise your voice. This is a sacred place. Now, you may not believe that, and I may not believe that, but, by God, it's a useful hypocrisy."

1) Doctor Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

When the subject you're making light of is the very real possibility that humanity will destroy all life on earth using nuclear weapons, is is even possible to handle with care? Perhaps that's why Doctor Strangelove persists as one of the greatest comedies of all time, because it had the cajones to poke fun at the arms race barely a year after Kennedy and Kruschev nearly blew everyone up over some missile parking spots in Cuba.

With the film's superpowers run by guys named President Merkin Muffley and Premier Dimitri Kisov, and Slim Pickens starting armageddon with a bit of atomic rodeo, Doctor Strangelove can be Looney Tunes levels of zany. Underneath that, though, is the creeping fear that such a farcical end to the world doesn't seem all that crazy. It's equal parts terrifying and cathartic. While everyone else was holding their breath, watching the clock tick down to midnight, Stanley Kubrick and company decided to let out a big, noisy fart. If you're going to die anyway, might as well do it with a smile on your face.

Cynical Soundbite: "Mr. President, I'm not saying we wouldn't get our hair mussed. But I do say no more than 10 to 20 million killed, tops. Uh, depending on the breaks."

What Makes For A Memorable Movie Trailer

Originally Posted on March 30th, 2012, at Playeraffinity.com

As far as introductions go, there are few as tightly controlled and crafted as the trailer, that vital piece of marketing designed to first expose a viewer to a film. Considering that trailers often determine the fate of multi-million dollar projects, it’s no wonder these three-minute elevator pitches have become just as important as the films they represent.

Trailers themselves are an odd media, as they’re one of the rare forms of advertising that’s actually enjoyed, and actively pursued, by their audience. In a sense, it’s an advertisers dream come true, as the proliferation of bite-sized media has not only widened the reach of trailers, but also created means for potential customers to willingly watch clips designed to invoke their purchasing power. Even the anticipation of trailers has reached ludicrous new heights; what does it say when movies such as Prometheus and Total Recall start their campaign with a trailer for the trailer?

The fetishizing of promos has clear drawbacks, as the pressure to deliver on an engaging snippet is made all the more difficult because of heightened—and often contradictory—audience expectations. A good trailer makes the viewer interested in novel ideas, but also plays to their established tastes (explosions, laughs, gore, etc.), a conflict that forces the editor to create a trailer that’s equal parts highlight reel, and curiosity stoker.

The temptation is to grab audiences using a little peek at the film’s big moments. Think about how many trailers now climax with a shot of a building falling over or something big blowing up. Of course, the danger there is that you’re giving the goods away for free, a bit like eating the frosting before putting it on the cake, and the final product is going to suffer because nothing will possibly be as good as that first taste. On the other hand, focusing on dramatics and the turns of a story won’t spoil the big moments, but it can hamstring enjoyment of the narrative.

Although often maligned for its transparent detailing of the plot’s major twists, trailers for 2005’s The Island showcased an identity issue formed from a radical second act twist, one severe enough to effectively split the film in two. It’s a case in which the editor has chosen advertising accuracy over secrecy, sacrificing not one, but two major plot developments to prep audience expectations accordingly. In truth, it’s a representative trailer. The mysterious and authoritative utopian setting is scrapped after the film’s opening act, replaced by CGI-laden chase scenes through a near-future city that’s perpetually at sunset.

So in other words, a Michael Bay film—but that’s not meant to be insulting (I swear). By citing Bay’s summer blockbuster credentials with mention of The Rock and Armageddon, the trailer for The Island creates an expectation from any audience member who’s even vaguely aware of the director’s style of filmmaking. Had the trailer focussed less on the pedigree, and held off on spoiling the big surprises, it would have made for a more engaging ad, but not a better viewing experience. Audience members enticed by the question of “what is the island?” would no doubt be jilted when they found out they had paid for a pristine future-conspiracy thriller that’s only 45 minutes mystery, and another 90 minutes bombastic fireworks/slow-mo camera rotations.

It’s also a case in which multimedia marketing comes into play; high concept sci-fi doesn’t translate to a 30-second TV ad quite as succinctly as “Michael Bay, Scar Jo, explosions!” Film advertising has long had a tendency to emphasize a movie’s flashiest moments in order to create a lasting impression, because when it works, it’s the difference between an ignored bomb, and a big hit. Promotional material for 2008’s Cloverfield heavily played up scenes of a devastated New York cityscape, along with the memorable image of a decapitated Lady Liberty. Cloverfield delivered sufficiently on the destruction teased, but when your film doesn’t have the budget for trailer shots emphasizing spectacle, intrigue is your best substitute, something Cloverfield had in spades.

With not even a title attached to it, the first trailer was a master class in sucker-punch setup, creating a cast of characters for one kind of movie, and then throwing them into an alien invasion, or a monster attack ... something, you're not sure what. Point being, you had to know what happens next. With just a taste of what was to come, the editors stoked public excitement by making them ask questions, and nothing keeps buzz going like curiosity. What happened to the Statue of Liberty? What is Cloverfield? And just what does this thing look like? Compare that to, say, John Carter, which was all spectacle and no speculation (other than “who the hell is John Carter and why should I care?”), and you can see how important it is for advertising to indulge our desire to see the blanks filled in.

Cloverfield managed to translate a need for answers into serious box-office returns, but the film’s positive reception came from delivering on the major promises made by the trailer. Although it’s never clear why it’s on the warpath, or what exactly the title is in reference to, the expectation of a big, cool-looking monster attacking New York was met.

But any good setup demands a proper payoff, and playing your cards too close to the vest can mislead audiences, or worse, make them feel like they’ve been fooled. Early spots for Inglourious Basterds were selling a hyper-stylized WWII action film in the grand tradition of previous Tarantino revenge films, but the final product was more a deconstruction of the medium than a gleefully sadistic gnatzi-killin’ good time.

Whereas Basterds was largely able to get away with its bait-and-switch advertising, other films aren’t quite so lucky. Drive ads caught eyes with their combination of brutal violence and synth pop-backed existentialism, but when audiences discovered that the film favored the latter greatly over the former, they were not pleased. Despite glowing critic reviews, the audience backlash over the deception was so severe it resulted in small box-office returns, and led one viewer to sue the film’s distributors over their “failure” to deliver the Fast & Furious-caliber action flick hinted in the trailers.

Granted, the braying of one crazy person shouldn’t condemn editors to absolute authenticity in trailers, but if trying to mislead the audience for the sake of subtlety is treated as false advertising, what’s the alternative? Is there middle ground between a straight plot summary and a curiosity factor? What it really boils down to is control of context, being able to show the audience what will happen in the film without them realizing what it all means until they’ve bought a ticket.

Now, I’ll plug Inception at every reasonable opportunity, but I can’t think of a better pair of previews than the teaser and official trailer produced for Christopher Nolan’s absorbing sci-fi masterpiece.

Much like Cloverfield, the dialogue-free first footage of Inception was primarily used to seed questions. How can a mind be a crime scene? What's going on with the gravity? What does "Inception" mean? It would be more than half a year before the first full-length trailer was released, but the sparse plot details provided only magnified audience interest. We’re told that Leonardo DiCaprio’s character is a specialist in mental security, and that dreams in this universe are somehow accessible. Beyond the introduction of such a novel concept, the trailer also helps us to understand the motivations of DiCaprio’s character, before showcasing a knockout montage of seemingly disconnected, yet memorable setpieces.

Anyone who’s seen the movie will pick out massive spoilers played out right in front of the audience’s eyes, but it’s all about context. The final act’s snowy hospital and ruined city settings are all heavily featured in the trailer, but we don’t have the slightest clue as to their import without seeing the rest of the movie. And like a lot of great trailers, the editors twist the context of pieces of dialogue to give an impression of the film that, while not entirely true, prepares the viewer for what’s to come. We know that DiCaprio’s goal is to return home, but the revelation early in the film that the woman hinted at in the trailers isn’t actually alive only deepens the mystery during the first viewing.

Similarly, the dramatic tension of the movie is bolstered when it is revealed that the definition of "Inception" established by the trailer is actually simpler than the real ambitions of the film. It’s not so much a bait-and-switch as it is a reinterpretation of the film’s actual content, which upon viewing, satisfies the expectations created by the advertisements, while also expanding on those expectations. It makes the experience of watching the film refreshing in the way that watching the trailer for the first time was, and that's how you know a trailer has been well-made.

Why I Secretly Hoped "The Amazing Spider-Man" Would Fail

Originally Posted July 9th, 2012, at Playeraffinity.com

I like Spider-Man. Who doesn't? He's Spider-Man: he does whatever a spider can. He's a cultural icon, and people who wouldn't be caught dead with a comic book come in droves to see the movies starring ol' web-head. Sam 2002's Spider-Man was a good start for his movie franchise, and Spider-Man 2 set a high-bar for superhero movies everywhere. I even think Spider-Man 3 gets dumped on more than it rightly deserves. So unlike a lot of people, I was cautiously optimistic when Sony announced they'd be making a fourth movie.

The newest entry in the series, The Amazing Spider-Man, may not have carried over any of the original talent behind Sam Raimi's trilogy, but there's still a lot to like here. Andrew Garfield looks the part more than Tobey Maguire ever did, and getting someone as impossibly cute as Emma Stone too play Gwen Stacey was a smart choice. And I really liked Marc Webb's directorial debut, (500) Days of Summer, which seems to have informed a lot of how Webb's approached this multi-billion dollar franchise. Reviews have been positive, and what started out as an 11th hour dead-sprint to the shooting lot has turned out to be adequate summer fare that I'm probably going to go see.

All that being said, part of me wants this movie to fail. That's a pretty shitty sentiment to have, considering the amount of time and care that no went into making the movie (no to mention the jobs that will hinge on its financial success). It's not one I like to have about any movie, unless I think its an unmitigated piece of garbage, or that a win for this one film will come at the cost of those to follow. The Amazing Spider-Man most certainly falls into the latter category, because while it's great that Sony seems to have found a way to differentiate a Spider-Man reboot enough from its predecessors to justify its existence, fortune favouring the reanimation of a franchise corpse that's barely cold sets a worrying precedent for things to come.

It's been no secret that The Amazing Spider-Man exists for reasons other than that it's going to make a bajillion dollars. It's really more about the potential bajillions that could be made with more Spider-Mans. Sony's control of the movie license requires that they make an actual movie out of the property within a certain amount of time, or the rights will default back to Marvel, like they did en masse after a gold rush on comic properties began in the 90's. It's the same reason that "X-Men" movies continue to get released, despite their increasingly tangential link to the original trilogy.

The legality wrinkle explains why Spidey was AWOL while Manhattan was an alien tailgate party during The Avengers, despite the serious bank Marvel Studios would have made with just a cameo. The depressing part is that Sony is basically treating Spider-Man like a toy they have no interest in until their little brother wants it, and then just play with him so that no one else gets to. What's concerning is whether an unspectacular but nonetheless strong debut for The Amazing Spider-Man will inspire other studios to pump out unnecessary sequels/prequels/reboots simply to keep the keys to a franchise.

Christopher Nolan's 'Batman' trilogy is on track to deliver the coupe de grace final chapter in its story that Spider-Man couldn't, but that hasn't stopped Warner Bros. from already talking about rebooting the franchise. Since Warner and DC are nice and cozy under the Time Warner umbrella, there's less legal wrangling at play here, but it's still insane that more than a year out from audiences getting some closure, Warner's attitude is "let it ride!" Even proven failures are getting second lives; Josh Trank, the director behind the inventive and original superhero movie Chronicle, got the chance to join the big leagues by being offered the chance to direct a Fantastic Four reboot. The lesson: if at first you don't succeed, make a sequel. If that fails too, wait five years and hope everyone forgets that the original sucked every which way but at the box office.

Comic books dominate the reboot discussion because it's inherent to the material. Right now, there are seven different lines of comics starring Spider-Man, either in solo fares, as part of a Marvel team, or inhabiting an alternate continuity. The almost non-existent regard for franchise distinction and the space-time continuum means there's no lack of source material for studios to pick from, especially for characters as old as Peter Parker and the dark knight. With so many different story permutations and character tweaks that have built-up over the years, it's not hard to see characters like Wolverine, Spider-Man and Batman becoming James Bond-esque movie properties, where a new instalment sticking to a few core themes and ideas comes out every few years, from a slightly different creative angle.

That in and of itself isn't a terrible idea in the short-term, but eventually, the choice to make the films will be even less dependent on earnest audience interest and the existence of comic book movies will be self-perpetuating, which hasn't always been great for 007. I dare you to find someone who's favourite Bond movie came out between The Spy Who Loved Me and Licence to Kill. When this train of thought crosses over into franchises not based on continual reinvention, it'll be like when the pig flu combined with the bat flu in Contagion: mass destruction on a global scale.

Okay, that's a little overdramatic, but it'll suck hard regardless. One of the movies I'm looking forward to the most this year is The Bourne Legacy, the sequel to the most consistent trilogy of action films pretty much ever. It doesn't have franchise star Matt Damon, or director Paul Greengrass returning, but it does have franchise writer Tony Gilroy taking over for the latter. The layperson won't give a hot damn who Gilroy is though, so the success of "Legacy" will be judged on brand strength just as much as The Amazing Spider-Man. From there, it's not hard to envision Gilroy leaving the series and someone else taking over, turning the franchise into a creative husk of its former self that gets by based on name-recognition.

Well, that's also being pretty worst-case scenario, as there's no reason to think that just because a property's reigns have been handed over to someone new, it's all a business transaction devoid of any inspiration. Part of what makes a series or character great is that they lend themselves to innovative and original stories within their identifying framework. So really, what I'm asking for isn't less of these movies, just that they happen at a slower rate. Give audiences time to miss seeing Spider-Man and Batman on screen, and let their returns occur at a time when it will actually mean something. At the very least, make a movie for reasons more compelling than legal ones. Spontaneity is great for a relationship and routine is a killer; if we start expecting a warmed over rehash of familiar franchises every five years, we'll just have to start looking somewhere else for new entertainment.

The Amazing Spider-Man is Basically Batman Begins

Originally Posted July 12th, 2012 at Playeraffinity.com

I can pretty much guarantee that right now, as you're reading this, two people are arguing over who's better: Spider-Man or Batman. Comparisons are a fun outlet for expressing our appreciation for pop culture, but the answer is always personal, not scientific. After all, one character is a Marvel comics property and the other is THE GODDAMN BATMAN.

The movie-based version of "who's the best" is heating up, with Spider-Man getting a new movie last weekend, and Batman wrapping up his trilogy of films in just a few days. While most comic book fans are still holding their breath for the dark knight's swan song, The Amazing Spider-Man is a perfectly fine reboot of the "Spider-Man" fiction, but that's because it's basically the exact same movie as Batman Begins, give or take a hyphen. The number of plot points and means of re-establishing the fiction that Spidey borrows from Batman's reboot is astounding, and if you don't believe me, check just a few of these uncanny instances of overlap between the two franchises.

And yes, here be spoilers.

Pair An Up and Coming Lead From Overseas With a Promising Genre Director

True, new Spider-Man Andrew Garfield was born in LA, but he grew up in Sussex, England, where he passed his British citizenship exam by appearing in a 2007 episode of Doctor Who, before garnering critical acclaim in The Social Network. Welsh born Christian Bale made a name for himself in indie and cult films like The Machinist and American Psycho, but his only experience in blockbusters before becoming Batman was opposite Matthew McConaughey in Reign of Fire. Point being, planning a new franchise for the long-term means getting a young, baggage-free actor with proven theatrical prowess.

Meanwhile, Marc Webb and Christopher Nolan both made their breakout features outside the realm of blockbusters, before quickly being given the keys to two of the biggest movie properties ever. The debuts for both influenced their respective superhero flicks: (500) Days of Summer's twee cuteness infected Peter and Gwen's relationship in The Amazing Spider-Man, while Batman Begins carried over Memento's thorough plotting and noir elements. You could also point to both filmmakers choosing to rely more on realistic stunts than CGI for directorial similarity, but let's dive right into the story.

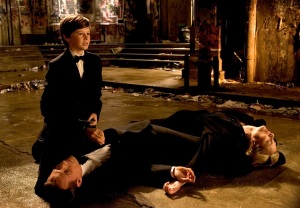

Start With The Hero As A Child Experiencing A Character Defining Moment

Swap the openings of "Begins" and "Amazing," and nothing much changes. Both have the young hero playing at home before experiencing a key moment of trauma. In Bruce Wayne's case, he falls down a well and is assaulted by bats. For Peter, the saddest game of hide and seek ever ends with a break-in at the Parker residence. The cause is Richard Parker's research into spiders (you can tell because there's a doodle of a spider on their chalk board, like real scientists make), which forces Ma and Pa to leave Peter with Aunt May and Uncle Ben before going into hiding…or something. It's all pretty vague. Anyway, each incident creates a key trait for the hero: Bruce becomes afraid of bats, while Peter's abandonment makes Richard's arachnid research a lasting link between the wayward father and son.

Make The Iconic Death The Result of the Hero's Flaw

Spider-Man's big motivation has always been the death of Uncle Ben, which he could have stopped in the 2003 movie, but didn't, because he felt like being a dick. The update has Peter's identity crisis, a theme the film beats you over the head with repeatedly, result in Ben's death. Peter spends too much time at the OsCorp research lab learning about his father, gets in a fight with Uncle Ben over his abandonment issues, and storms off into the night, with Ben following. A bottle of chocolate milk and an armed robber later, and we've got one dead uncle and a seriously guilt-ridden Spidey.

Which isn't all that far off from what happens to Thomas and Martha Wayne in Batman Begins. Fear is the theme de jour this time, and while Batman's parents still get gunned down outside a theatre the way they always have, it's Bruce's fear of the Cirque de Soliel guys looking too much like bats that causes the family to leave early, and exit out into the incredibly sketchy alley built into the fancy opera house. If Peter had had a handle on his orphan angst, and if Bruce had just (Bat)manned up, there would be no call to a life of vigilantism.

Develop The Costume Piecemeal

Both Spider-Man and Batman spend their first nights on patrol dressed in duds courtesy the local Salvation Army before really developing their signature looks. Spider-Man uses a heavily modified spandex speed skating suit, while Bruce Wayne assembles his armour from Wayne Tech inventions and items ordered through the company in bulk, so as to avoid suspicion. Apparently the police are less likely to suspect the guy with thousands of bat-shaped masks of being Batman than the guy who has none. Speaking of which…

The Police Hate The Hero

Just to stack the deck against our protagonist before the big bad is revealed, Spider-Man and Batman end up on the wrong side of the law they're trying to enforce. In Batman's case, it's because many of Gotham's finest are in the pocket of organized crime, whereas Spider-Man manages to piss off every cop he encounters by showing how completely inept they are. There's always that one good cop on the force though, but more on him later.

Promote A B-Tier Villain Into A Mentor/Father-Figure Related To The Parents' Death

The problem going into The Amazing Spider-Man was that all the classic villains had been used in the original trilogy; what remained were a bunch of one-note high-school basketball mascots like Rhino and Scorpion, of whom the Jekyll and Hyde-ing Lizard proved to be the least ridiculous. Meanwhile, pre-Batman Begins, pretty much no one would be able to tell you who Ra's al Ghul was, much less pronounce his name. The purpose of choosing newbies as heavies was two-fold: first, it distinguished the new films from the old ones, and second, the leeway allowed by having an unknown villain meant they could become a foe that helps better define the hero.

In each film, the hero is taught under the wing of an older mentor who knows of their tragic past, before said mentor reveals their true intentions. They're also responsible for the death of the hero's parents in some way. Ra's' League of Shadows plummeted Gotham into the recession that got the elder Wayne's killed during a mugging, while Kurt Conners, the Jekyll to Lizard's Hyde, worked with Peter's father before betraying him to the conspiracy that killed them…or something. Seriously, I cannot overstate how ill-formed the parent conspiracy plot is. The ultimate result is that the hero fighting the villain is as much about getting a little parental payback as it is stopping an attack on the city, which in both cases just so happens to involve...

The Villain Attacks the City Using Chemicals

Blowing up a city with bombs? Too cliche. Holding the city ransom with a giant laser? Too tacky. Today's villain is all about dispersing clouds of chemical agents through downtown. And both Lizard and Ra's have enough flair to spice up the attack with some thematic consistency; in the latter's case, the green fog falling on Manhattan turns folks into human-animal hybrids, while misty white fear gas gives Gotham's citizens a deadly case of the heebie-jeebies. Our hero is immune to the stuff but what about his policeman sidekick? Well good thing…

The Love Interest Will Provide An Antidote For The Good Cop

The love interest, in addition to having worked with one of the villains at some point, and learning her super-suitors identity by film's end, will be the only one available to give the good cop the antidote he needs to help the hero save the day. Rachel Dawes inoculates Sgt. Gordon from the fear gas, allowing him to set up Batman's big train derailment. Gwen Stacey, on the other hand, gives her father, Captain Stacey, the counter-agent to Conners' mutagen, which he hands-off to Spider-Man before blowing a few chucks out of The Lizard. It's a dramatic finale, made all the more so because…

The Climax Is Staged At A Place of Familial Importance

Not only does Peter Parker have to defeat his father's old lab partner at the end of The Amazing Spider-Man, he does so on the roof of the OsCorp building, where Richard Parker did the research that got he and his wife killed, and developed the spider that gave Peter his superpowers. Batman meanwhile gets a double dose of daddy-issue resolution, by fighting Ra's not just on the train that Thomas Wayne built, but one that just so happens to be on a collision course with Wayne Tower. Congrats guys, you made your daddies proud by defending their homes away from home, which is all the more impressive because…

The Hero Is Seriously Injured Before The Final Battle

When running up against an 8-foot tall reptile or a martial arts master, chances are that the guy with his name in the title is going to win the final showdown. Since the hero's victory is an inevitability, the only thing to do is make it seem more difficult by forcing him to fight wounded. Batman suffers a nasty gash to the body, courtesy a flaming log, before confronting Ra's, while Spider-Man gets winged in the leg by a crack-shot cop who fires at ol' webhead, despite being given explicit orders not to shoot Spider-Man only two seconds prior. In both cases, the injury doesn't really factor into the final conflict, but it does heighten the stakes during the build-up.

Promise A Bigger Bad Guy Next Time

Having successfully dusted off his wings and reintroduced the caped crusader to the world, while also having turned a no-name villain into a memorable on-screen adversary, Batman Begins ended with a hint that the most legendary villain of the rogues gallery, The Joker, was coming next. It was the perfect note to end the film on, having blown audiences away before teasing that "you ain't seen nothing yet."

And The Amazing Spider-Man tries to do the exact same thing. An after-credits sequence has the newly imprisoned Kurt Conners pleading with a nefarious unseen figure to leave Peter Parker alone, as he appears to be further up the chain in the Parker parent conspiracy. This points strongly to the next villain being…Norman Osborn? Mysterio? Hell it could be J. Jonah Jameson for all we know: most newspaper horoscopes are more accurate and informative than this bit of half-baked sequel-baiting.

It's the last, and certainly most laughable, example of The Amazing Spider-Man trying to pull from Batman Begins' playbook, only to come up with a handful of empty webbing. What Marvel didn't seem to get is that the reason we compare Batman and Spider-Man is because they're distinctly different, and as such, deserve different movies. Imagine a dancing, emo-haired Batman, and tell me I'm wrong once you've stopped vomiting.

Six Things We Want From Avengers 2

Originally Posted May 8th, 2012, at Playeraffinity.com

What little doubt remained over Marvel’s grand experiment of merging all its comic book franchises into one summer blockbuster pretty much evaporated this weekend, when The Avengers took audiences and the box office by storm. After being hinted at and set up over four years worth of superhero movies, the unprecedented collaboration paid off big time (+$200 million in 3 days big), and now Marvel is prepping for phase 2 of its theatrical master plan.

While those plans include an Iron Man 3, and sequels to Thor and Captain America (and maybe even a new Hulk movie), the golden goose continues to be The Avengers, and with earth’s mightiest heroes having earned some downtime following their explosive introduction, it leaves it to fans like us to speculate and guess what the future holds for Marvel’s flagship franchise. Here are a few suggestions to make sure that the future of this ultimate crossover doesn't become the story of a one-hit wonder, and if you’re among those few who have yet to actually see The Avengers, be warned, as minor spoilers follow.

Keep Joss Whedon as Writer and Director

This is definitely the most important factor determining the franchises’ future. The actors have all signed on for multi-film deals, but a return for writer and director Joss Whedon is still in question. The announcement of his involvement in The Avengers was the first big indicator to fans that Marvel was taking the project as seriously as they should have, and it’s hard to envision anyone having more clout in geek circles than Whedon. His TV background certainly didn’t hamstring the film’s flashy visuals, but it’s his ability to create a sympathetic character out of just about anyone that allowed The Avengers to be more than just a big dumb action movie. He’s just a fantastic storyteller, and anyone looking to fill his shoes will be hard pressed to accomplish anything half as charming, emotional, and well-constructed as what Whedon did in The Avengers.

Expand the Team

While Marvel will definitely be trying to get some of its lesser known heroes into their own pictures before Avengers 2 (Edgar Wright sounds like he’d give-up his first born to do an Ant-Man movie), that shouldn’t limit the roster to just folks with a film under their belts. Hawkeye and Black Widow were successfully integrated as full members of the team despite previously only appearing in cameos, but the Avengers have had such a huge and constantly changing roster over the years, that throwing in a B-team wouldn’t hurt. The X-Men movies proved that audiences can get a quick handle on superpowered second-string heroes, so there’s no reason folks like Wasp, Black Panther, or Ms. Marvel can’t make their debuts here. Keep them around as side characters or cameos that can bounce off of the founding members, or be used as cannon fodder. Speaking of which...

Create a Greater Sense of Danger

By the time The Avengers rolls into its last act, and the team has finally assembled, it’s hard to imagine anyone or anything stopping them, whether it’s an alien army, or a malevolent demigod. Yes, the death of Agent Coulson was sudden and wrenching (in other words, classic Whedon), but we need to really see our heroes in danger if the pay-off for their triumphs is going to be exciting. Of course, killing off any of the big four would be crazy when they have their own franchises to carry, and already there are rumours of Black Widow and Hawkeye getting their own movies, but by the time Avengers 2 finally arrives, it may be time to dispose of a few members in the returning cast. It might sound harsh, but a surprise death or two would really raise the stakes, and help shore up the dramatics in a series that’s already mastered being fun.

Let’s See Avengers Tower

The end of The Avengers leaves Stark Tower in desperate need of some renovations, and it’s hinted at that the skyscraper will become the team’s new base of operations. While the S.H.I.E.L.D helicarrier was a decent enough place to bring all the Avengers together, it’s made abundantly clear that an aircraft housing guys like Hulk and Thor is pretty dangerous when 50, 000 feet in the air. Putting them up in Avenger mansion would be a definite downgrade from a flying fortress, so the Tower is easily the most stylish option from the source material. Giving the team a place to call their own would help maintain the sense of community amongst the superfolks, and would be a great location to fill with little Marvel Easter eggs, the same way Odin’s Vault hid clues in Thor.

It’s Called the Marvel Universe for a Reason

Watching Hulk steer a robo-centipede into Grand Central Station was pretty cool, but there’s only so many ways to blow-up a major metropolitan city. Moving the action out of New York, and even off-planet, would help capture the immense scope many of The Avengers’ best stories have. Thor did a great job of simplifying the complicated Norse mythology behind the God of Thunder so that instead of being some sort of deity, he and his fellow Asgardians were essentially just space vikings, creating a precedent for galaxy-spanning adventures. It doesn’t have to be The Avengers: Mission on Mars, but exploring the wider reaches of the Marvel Universe even just a bit would really solidify the franchises’ reputation as an adaptation true to the source material.

Handle Thanos with Care

So unless you’re well-versed in your comic book lore, you were probably wondering who the smirking purple space ape in the non-shawarma related post-credits sequence was. That was Thanos, a death-worshipping alien from Saturn’s moon Titan, and he’s among Marvel’s biggest bads. Having him as the villain in Avengers 2 would support a lot of the things we’ve asked for here: Thanos is an interesting, extremely deadly villain in the Marvel universe, and would present an unprecedented threat to The Avengers, but he’d also be a tricky adversary to pull off correctly. He’s literally obsessed with Death, the female personification of mortality, so his motivations are more than a little unorthodox, and his costume, even compared to the guy’s like Cap and Thor, is kinda ridiculous. We’re not saying he’d be impossible to recreate for theatres, it’s just that it might be hard for audiences to buy a pyjama wearing death-fetishist with a penchant for jewellery as being the greatest for to face The Avengers, so a little bit of tinkering to the established character might be necessary.

Six Ideas for Batman's Movie Future

Originally Posted to Playeraffinity.com, August 25th, 2012

As it's been pointed out for the better part of a month now, there's plenty to admire (or more bluntly, slavishly fawn over) about Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight Trilogy. He not only proved that people will pay a ton of money to see summer movies that are more emotionally and intellectually stimulating than $250-million dollar versions of Rock 'em Sock 'em robots, but also showed that a reboot can be a reinvention instead of just a rehash. And perhaps best of all about The Dark Knight Rises, is that it brings his Batman trilogy to a definitive end, granting audiences closure as he and Christian Bale ride off into the sunset with no intention of even returning to Gotham...

...which is probably why some Warner Bros. exec is currently pulling his or her hair out trying to decide what to do next, since Nolan has burned down the franchise torch so close to the handle, whoever he passes it on to next is going to get burned. Where can Warner possibly go after the unparalleled success of The Dark Knight Trilogy? Is it time to hit the reset button and start from scratch, or see where the few threads left dangling may lead?

Here are a few different thoughts and angles to consider now that the prospect of making a great new Batman movie seems even more daunting than after the boondoggle that was Batman & Robin. First, let's explore the many possibilities of rebooting the Caped Crusader, then discuss the options for a slightly more direct sequel to the trilogy. And if you're one of the three people who hasn't seen "Rises" yet, prepare to have it spoiled.

The Reboot Route

Distance Yourself From The Nolan Films As Much As Possible:

One of the biggest problems with Marc Webb's recent superhero reboot, The AmazingSpider-Man, is that it's aesthetically indistinguishable from Sam Raimi's original trilogy, and offers only slight changes in tone and characters to get us through the same origin story we've already seen. Having to watch two Batman origin movies in the same decade would suck, as would trying to make a reboot in the vein of The Dark Knight Trilogy. Whoever winds up following Nolan will inevitably be ill-equipped to recapture his kinetic, more realistic take on Batman, so no one should even try.

The best course of action will be to either take an approach that's either much lighter, or even darker. As for setting up the character, any reboot would be wise to alter the traditional story heavily, or skip over it altogether. Whoever doesn't know that Bruce Wayne's parents got shot when he was young, and that he has a thing for bats, probably doesn't care about Batman in the first place.

Follow Marvel's Lead: Fun First, Brand Building Second

Sure, a lot of The Dark Knight Rises' success at the box office is due to it offering a darker, more mature alternative to Marvel's breezy and more gratifying superhero flicks, but Batman's been goofy a heck of a lot longer than he's been moody. A return to Batman's campier, but more accessible roots would help give a new film its own identity, while also giving DC the opportunity to build towards something they've wanted for years: a "Justice League" movie.

Marvel launched the "Avengers" initiative with Iron Man because he's the most relatable and charismatic character in their roster; the same could be said of Batman for The Justice League. While next summer's Man of Steel is rumored to get the team-up ball rolling, early teasers make it appear nearly as grounded and serious as Batman Begins was, and the whole point of crossovers is that they're meant to be fun and exciting, something The Avengers did really well.

To wit, i'm going to say three words no one wants to hear: bring back Robin. It's really easy to hate The Boy Wonder, even Christian Bale said he wouldn't do a Batman movie if Robin was in it, but Batman having a sidekick makes him part of a team, which is what The Justice League is all about. A young companion helps to lighten the tone, and means Bruce Wayne's past doesn't have to be the main through line all over again.

Make The Darker Knight

It's hard to imagine a PG-13 rated superhero movie that's somehow bleaker than one in which love interests tend to die horribly and the hero's hometown does a six month LARP of Berlin circa 1945, but Batman's source material has some seriously grim alternate versions to draw from.

Take, for instance, Batman: Earth One, the newest comic to modernize Bruce Wayne's originsby reimagining the death of Martha and Thomas Wayne as political assassinations, and Gotham's police force as completely at the mercy of organized crime. Best change: prim and proper butler Alfred gets turned into a gun-toting S.A.S. badass, who trains Bruce in crime fighting, even though he should probably be the one out on the streets cracking skulls in the first place.

Or Warner could revive their original plans for the post-Schumacher era and use Darren Aronofsky's plan for a "Batman" that's part Se7en, part Dirty Harry. Instead of inheriting the Wayne estate, Bruce becomes a street rat under the care of an auto repairman named Big Al. For high-tech weaponry, Bruce has cobbled together junk, including an armoured Lincoln Continental straight out of Mad Max. While he slowly develops a secret identity that includes a hockey mask, Jim Gordon is a suicidal Serpico figure looking to violently end corruption in Gotham, and Selina Kyle is busy running a local cathouse. The latter option in particular would need something stronger than a PG-13, but a bump up in age rating is about the only way you'll out-dour Nolan.

The Sequel Route

Blake-man Begins

By conventional standards, the end of The Dark Knight Rises is about as sequel-ripe as you can get. With some instructions left by the presumed dead Bruce Wayne, hero cop John Blake finds the Batcave, and one can imagine Bruce also left a bunch of details on how to access all the hideout's special toys, and what day garbage is. Granted, it's unlikely that Blake is as well versed in martial arts as Bruce, but he's as determined to bring justice to Gotham as the original Batman, due process and civil rights be damned!

This leaves open a few options for Blake as the new protector of Gotham. John Blake does sound suspiciously like Tim Drake, a former Robin who started hanging out with the big boys once he ditched the red and green tights to form his own secret identity, Night Wing. Keeping on the name train, the reveal that Blake's full name includes "Robin" in it could mean that's the new identity in store for young John, although most superheroes will recommend coming up with an alias that doesn't actually contain parts of your real identity.

The obvious direction would be to have Blake go for the brass ring and become the next Batman. It'd be a clever way of acknowledging that the title can pass not just from actors, but from characters too. Plus, they could follow Grant Morrison's recent run of Batman & Robin comics where a (temporarily) dead Bruce Wayne is replaced under the cape and cowl by former Robin, Dick Grayson. The Robin shaped hole in the dynamic duo was then filled by Damian Wayne. Who's Damian you ask? Well to answer that, we should consider …

Talia Is Alive and Preggers

Here's what we know about Talia al Ghul: she's got serious ninja skills courtesy her father, Ra's, she and Bruce had an impromptu foyer fling (and considering Bruce's celibate streak, chances are the bat-condoms in his wallet were expired), and her death was about as convincing as Katie Holmes playing a district attorney. Unless we see a funeral, closing your eyes and slumping over doesn't cut it. During the climax of the movie, when everyone was busy watching Bruce re-enact his favorite scene from The Avengers, Talia could have easily slinked away somewhere safe to later discover she's going to have a Bat baby.

In the comics, Damian Wayne was the son Talia and Bruce, raised by the former to be about as nice as anyone could expect from a kid named Damian. But after some fast-tracked daddy issue resolution (i.e. Bruce dying), Damian settled down and became an official part of the Bat family, filling in Dick Grayson's shoes as Robin just as Grayson was filling in Batman's.

Imagine this then: Talia's shame at failing to fulfill Ra's plans for Gotham forces her into hiding, where she raises and trains Damian, preparing him for his legacy as the heir to both the League of Shadows, and Wayne Enterprises. With Bruce too busy completing his bucket list of countries to bone Catwoman in, a young Damian comes to Gotham to find the mysterious Batman his mother has told him so much about. When he finds John Blake instead of dear old dad, a more experienced, wiser John Blake takes Damian on as his ward, training a replacement that, like Bruce, has some serious family issues. It not only sets up a fresh story dynamic, but also seeds possibilities for more sequels, by having a future Batman waiting in the wings.

Take Batman Global

Speaking of Grant Morrison, before DC comics decided their continuity had become as tangled as Christmas lights caught in an airplane propeller and hit the ol' reset button on everything, Morrison started a "Batman" series that saw Bruce Wayne taking his fight against crime around the world. Batman Inc. had Gotham's guardian branch out across the globe, finding promising crime fighters to enlist as Wayne-funded protectors for their respective regions.

While Gotham has been the most important uncredited character in Nolan's films, it's taken quite a beating over the years, and increasing the scope of the "Batman" universe would help open new story opportunities. The Dark Knight already had Batman kidnapping an oily criminal accountant from China, so there's precedent for a Batman without borders. And last we see Bruce Wayne, he's out and about in the world, so who knows what new and exciting villains beyond the skyscrapers of Gotham need a good thumping from the original masked vigilante.