TIT for TAT is just that: Thoughts in Ten for This and That.

It's a running, rambling catalogue of what I've been watching. Mouse over the image and scroll down through the text to get the good word. All views delivered in ten minutes or less, or your money back.

Last Update: July 9th - The Rocketeer

July 2014: The Rocketeer, They Came Together, Shovel Knight, Masters of Sex S1E02, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, Penny Dreadful Finale, 22 Jump Street, Days of Heaven,The Martian by Andy Weir

When I left the 17-minute preview screening for Guardians of the Galaxy -a ridiculous marketing event designed to get word-of-mouth going on a movie Disney is wringing their hands bloody over (and one that I, admittedly, did feed into)-, I could tell the glorified ad’s job had been accomplished in a roundabout way. My desire to run out and see GotG was completely unchanged, which was a pleasant result, seeing as I expected the footage to either increase my hype levels to frustrating levels, or leave me despairing at having to rewatch a sizeable chunk of the movie again when it’s released in whole. I remain cautiously optimistic about Guardians, but the film I did want to run home and watch right away was Slither, the 2006 horror-comedy director James Gunn made before getting the Marvel gig.

Though I only caught up with it recently, I loooooove Slither, so much so that it’s one of the few films I’ve ever finished, then immediately hit the play button on again as soon as it ended. It was such a shockingly successful blend of tone and style that it became the main reason for me to be excited for Guardians of the Galaxy in the first place, seeing as it’s a comic property that would require a deft touch to translate to film. In light of the Ant-Man debacle, the fear is that Marvel and Disney are sanding off all the rough, weird edges of their movies in the name of keeping a homogenous house style, and without rough weirdness, there’s no point in making a Guardians of the Galaxy adaptation at all.

Anywho, that’s a really winding way of leading up to saying that, last night, with literally hundreds of movies and TV shows available for my viewing pleasures, I decide to watch Disney’s 1991 box office failure, The Rocketeer. The throughline of thinking here is that The Rocketeer was directed by Joe Johnston, who went on to make Captain America: The First Avenger more than a decade-and-a-half later for the very same house of mouse. And, at least for, the gamble on my evening paid off. The Rocketeer has become something of a hidden gem among those who remember the then-ambitious adaptation of the ‘80s graphic novel, a throwback to ‘50s adventure serials with the heart of a superhero story. Watching The Rocketeer, it becomes a completely obvious why Marvel wanted Johnston for Captain America, but it offers plenty to those uninterested in the genealogy of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The Rocketeer’s got Timothy Dalton playing a Nazi-collaborating Errol Flynn insert, Paul Sorvino in full old timey gangster mode, and even Margo Martindale as a pan-wielding, no-nonsense waitress; how was this movie not a massive hit?

Well, that’s not that hard to figure out, even excluding that its box office competition at the time was Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves and City Slickers. The Rocketeer seems a clear attempt to recapture the ‘40s nostalgia at play when Raiders of the Lost Ark made memories of The Greatest Generation into high-flying adventures, but The Rocketeer forgot to steal Indie’s bad boy charisma. That’s not to say star Billy Campbell is wrong for the starring role, quite the opposite; his boyish good looks and non-threatening charm are exactly what the character requires. The problem is that, this being a film from Disney, The Rocketeer is utterly earnest and without cynicism, which even for audiences in 1991, would seem a little hard to swallow.

Ironically, Disney has since gone on to buy Marvel, whose Iron Man and Captain America adaptations owe a lot to The Rocketeer, while Disney’s own attempts at throwbacks these days are a treacley mush. They got it right the first time in ‘91, as The Rocketeer holds up very well for any viewer interested in theatrical superheroics that’s also tired of the bloat swallowing the genre whole these days.

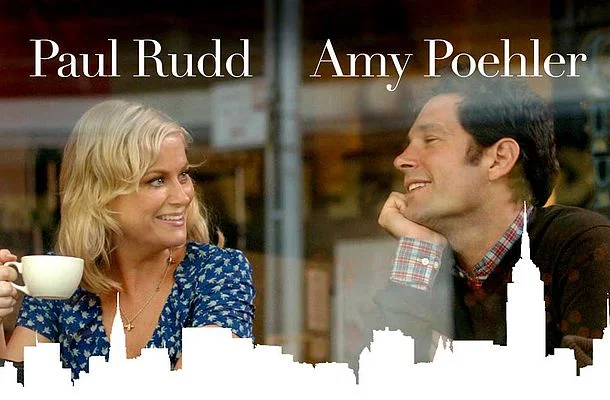

There’s been a lot of mixed word on this recently released rom-com parody starring roughly half of TVs best comic actors (and Paul Rudd). It’s been popping up on a number of mid-year lists under the conflicting banners of “Best Surprise” and “Biggest Disappointment,” due largely, I imagine, to the potential of the cast, and for being directed by David Wain. The film’s supporters are often those who share an open affection for Wain’s sketch-based style of directing, so the fact that I haven’t seen Wet Hot American Summer, and mostly like his work with more traditional comedies like Role Models and Wanderlust, meant I was largely unsure as to which camp I would fall in.

I can definitely see a strong case for both sides, as while it can be rip-roaringly funny, They Came Together makes its primary target a horse that’s already been thoroughly beaten. The romantic comedy has turned into a wheezing shell of a genre over the last couple decades, and it’s not like its tropes and foibles weren’t incredibly obvious back when the movies they were in were still good. Rudd and Amy Poehler star as a couple recounting their relationship history, introducing it by directly relating it in terms of romantic comedies. They Came Together is looking down on the films it’s lampooning from the first, but considering how cliché making fun of the rom-com genre’s clichés has become, the film can sometimes seem like it’s overly satisfied with how it skewers such low-hanging fruit.

Self-aware dialogue that explicitly states the beat in the script being shown isn’t really a parody when all you’re doing is foregrounding the subtext the audience is usually aware of when played earnestly in a legitimate rom-com. When going down the parody well, They Came Together is much, much funnier when picking out the smaller recurring elements of the genre, like an overabundance of holiday-themed parties, and the ridiculous financial irresponsibility of those eccentric businesses the female love interest usually works at. Maybe the funniest gag is one that sneaks up so quietly, you might not notice until the third instance, as at least a half-dozen scenes end with a character dramatically saying “shit!” after missing an opportunity to say something.

The limper material is always held aloft by Poehler, Rudd, and too many terrific ringers to count (can someone please give Jason Mantzoukas or Michaela Watkins a feature already?), but the film’s absurdist streak that makes it more familiar of something like, say, Airplane!, instead of an extended Funny-or-Die video, is where the best material is. There’s a Rake Gag that never has to cycle from being funny, to unfunny, to funny again, because each iteration made me laugh harder than the last. And when the movie does set-up a trope that’s well worn even by other parodists, like a dress-up montage, or a snooty waiter, the punchline is often over-the-top enough to take you by surprise. They Came Together may be divisive, but it’s so jam-packed with jokes that it has the makings of a cult classic for those who love it the first time, and may eventually wear down dissenters over the long term.

Vidya-games! One in particular really: Shovel Knight! Excuse me while I use every excuse to write out Shovel Knight, just so I can hear it again in my head. I mean, just say it. Shoooooovel Knight. It’s, like, “cellar door,” but for videogame titles.

Shovel Knight.

Anyway, Shovel Knight is a retro-throwback game on 3DS that’s been making a lot of waves recently, mainly because calling it both retro and a throwback is warranted. Plenty of titles over the last decade have tried to emulate the experience of playing an original NES game simply by imitating the look (thanks in part to an increasingly loose definition of “8-bit graphics”), but it’s the gameplay that matters most, which Shovel Knight absolutely nails, thus earning the title of legitimate throwback.

A frothy mix of Castlevania and Megaman, with just a little Super Mario that snuck in while no one was looking, Shovel Knight is a 2D adventure platformer that tasks the player with guiding the eponymous gallant gardener with traversing a dozen-or-so levels filled with traps, spikes, pitfalls and enemies, all leading up to boss encounters with knights of similarly over-specific categorization. Personally, Polar Knight was my favorite of the motely villains making up the Order of No Quarter (again, great name), seeing as he’s an oversized Viking that wields a snow shovel.

In true NES fashion, the controls are pixel perfect: wherever you want Shovel Knight to go, he can, provided you have dexterous enough thumbs to input the controls correctly. Shovel Knight is never a cheat when it comes to difficulty, which is perhaps where it helpfully adds a little modernization to the nostalgic love-fest. Checkpoints are frequent enough to make stages challenging but not maddening, and the game’s death penalty is forgiving enough to make failure something you want to avoid as a matter of pride, not lost progress.

The soundtrack is absolutely terrific, and the old school palette and pixels are just the outer coat of some really gorgeous presentation. Many of the boss characters move with exaggerated animations, and the town’s people scattered about your adventures are a lively assortment of oddballs. Most memorable of the bunch is The Troupple King, an excessively large figure of piscine royalty that’s half apple, half trout, all Troupple. He even dances.

Shovel Knight’s personality is often its strongest asset, eschewing elbow-in-ribs references to other games or bottom-feeding internet humor for a world crafted with honest to god inspiration. Even in the game’s archaic premise of trying to save the damsel, Shovel Knight finds ways to remix the formula that preserves the classic feel of a NES game, while smartly updating the design for modern standards. It took less than 6 hours to shovel my way to victory, but at a $15 asking price, this is a no-brainer.

Shovel Knight!

When Masters of Sex was originally announced, I knew I was onboard from the jump. Not only was the idea of a show dedicated to scientific research right up my alley, but the prospect of a cable drama not dealing with crime, terrorism, murder, the apocalypse, or just misery in general, felt like a bloody revelation. Add to that a period setting based on actual researchers, and Lizzie Caplan and Michael Sheen as the stars, and you pretty much couldn’t have come up with a more appealing show.

I watched the pilot when it premiered last year, liked what I saw, and….only just watched the second episode, due in part to the show’s quickly approaching second season. The pilot didn’t put me off when I first watched it -that I can remember much of it clearly a year later means they were doing something right. But committing to a new TV relationship requires a certain amount of effort I wasn’t ready to put in at this time last year, what with all the other shows that summer 2013 had to offer. 2014 has been a merciful reprieve in that regard (though it’s been offset by a really strong selection of films), so with the help of an informative “previously on,” there was nothing to hold me back from finally getting into Masters of Sex.

The lead paragraph maybe oversells the show’s uniqueness just a bit, as it has the early makings of an Anti-Hero drama, just in the Mad Men vein, instead of something more plot-heavy like Breaking Bad. Sheen’s Bill Masters is every bit the prickly hard-ass striving towards some Greater Good that Don Draper and Walter White always were, but thanks to historical precedent and a less directly self-interested goal, Masters sabotaging his life, and the ones of those around him, in the name of advancing human understanding of sexuality, actually has some weight to it.

The show is still very much in its infancy, such that I was hardly surprised to see episode two double down on the pilot’s double-entendre streak. That the opening credits for the show are nothing but Freudian imagery establishes the difficult approach the show has to maintain when dealing with its chosen subject matter. Sex is silly and spiritual, universal but also deeply personal, and depending on the person, the most important thing in your life, or the least. It would be just as inappropriate for Masters of Sex to treat sex like a snickering twelve year-old as it would to treat it purely clinically. Masters attempting to codify the rules and systems behind a concept of limitless definitions and variations creates an interesting juxtaposition for the show to play with out the gate.

Of course, the show can’t be all about sex all the time (though, one could easily argue that’s the whole point: everything eventually circles back around to sex), so the show does a pretty solid job of setting up a number of engaging characters and relationships over its first two hours. Most belong to the women, in particular Caplan’s Virginia Johnson, along with the salty working girl Betty, who ends the hour with a completely different identity than when she started. A significant improvement from the pilot is Masters’ current wife, Libby, who’s perhaps the most outright sympathetic Anti-Hero wife of any recent examples of the trope. She would most certainly need to be written as a cold-shrew in a two-hour film that looks to follow Masters’ personal history accurately, but using a serial format, the show can explore the complications of their relationship for all they are worth.

Whereas the sexual symbolism can get a pass, the show’s thematic stop signs are more than a wee bit on the nose still, but it’s early hours. There’s a lot of potential for this show to break new ground for TV, and I look forward to seeing what’s in store for the rest of the first season.

With a screening for Dawn of the Planet of the Apes just around the corner, a revisit of Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Rupert Wyatt’s unexpectedly successful prequel/reboot, was necessary. I missed it in theaters, but after viewing it on home release was just as surprised as everyone else to learn that the Apes series was not only still relevant in 2011 (especially in the shadow of the execrable remake from 2001), but that it had such wide box office appeal.

A rewatch hasn’t done much to change my opinion on Rise, though that means maybe it deserves even more credit for the often-seamless motion-capture technology bringing the ape characters to life. The naturalism to Andy Serkis’ performance as Caesar is the keystone for the film’s success both emotionally and financially: for better or worse, audiences are much more sympathetic towards on-screen animals than they often are to most humans, even when the humans aren’t written as so in need of a comeuppance as the ones in Rise are (there’s an audacious misanthropy to having your closing credits showcase most of the world’s human population being wiped out by a virus).

Wyatt could have easily capitalized on this alone to make the film a self-loathing Nature’s Revenge film, a la Godzilla, wherein we kinda get off on the (safely theoretical) premise of humanity’s destruction of earth being forcibly balanced by other inhabitants of the planet There is, of course, an element of that here, but the script and Serkis’ performance make Caesar a captivating and tragic figure all on his own. The brilliant prison-break structure of the film’s mid-section transitions the character from pitiful Andy Dufresne to a charismatic Spartacus, and the 20-minute climax on the Golden Gate Bridge is refreshingly focused for a blockbuster finale; no ticking time bombs, no secondary squad of characters trying to achieve another goal, just a good, clean mad-dash to freedom.

The second viewing did further reveal the ironic contrast between the heightened intelligence of the apes, and how generally dumb Rise is as a film. It treats scientists like magicians with trendier set designers (making occasional overtures towards a theme of “look at man’s hubris!” incredibly grating), which is pretty much par for the course, but even cursory analysis of the plotting on a scientific, geographic, or temporal level reveals a story riddled with inconsistency. It doesn’t really matter though; Apes is a ridiculous premise, but it explores emotional truths about people and our world in ways that all good science fiction should.

Yesterday went from Eva Green Withdrawal Day to Manly Men on Boats Day faster than you can say “300-Rise-of-an-Empire-Master-and-Commander-The-Far-Side-of-the-World-double-feature.” I’ll get into more detail about my thoughts on the former in a blog post, but catching up with M&C:TFSotW (God, even the acronym is unwieldy) has made it clear why the 2003 tale of seafaring derring-do maintains a healthy reputation among the seemingly few who actually remember it (a certain, more pirate-focused vehicle from Disney that released a few months before it sucked up most of the oxygen and attention of nautically-inclined audiences).

Macstander: Side World is a movie for dudes. That’s not to say women can’t or shouldn’t enjoy it, it’s just that like, say, The Shawshank Redemption, it’s a film of only men, living in world of only men. Instead of a prison, Master Mander is set on an English man-of-war pursuing the hated French at the dawn of the 19th century. With a crew of 119 men aged from pre-pubescence to retirement, led by Captain Jack “Lucky” Aubrey, the manliest man of them all (played by Russell Crowe, of course), the film constructs a makeshift and entirely masculine society bound by close-quarters, and confined there over long periods of time.

As a historical epic, it’s really engaging to watch, giving a time-traveler’s tour guide of naval technology, culture, and organization. More specifically though, Commander World is an extremely effective exercise in Bro-manticism: it’s got massive ship-to-ship combat and gunplay for the action-hounds; it’s got the wide-eyed wonder of exploration that any kid with a backyard has ever felt; it’s dramatically rich in themes and speeches about duty and brotherhood; and, most importantly, it’s got Crowe’s Aubrey, a character who’s all men to all men. He can be stoic and badass, or boorish and bro-y depending on the scene, a man who both inspires the younger men under his command, and is himself humbled by the greatest man he ever knew, Admiral Nelson. Whereas most big budget films try to cover four quadrants, director Peter Weird seems to have gone out of his way to make sure male viewers from any decade will have something or someone to latch onto here.

And it totally works. Gary Larson’s: The Far Side casts such a wide net of male-interests within its microcosmic narrative that you can’t help but get swept up in the excitement. My particular point of weakness was Paul Bettany as the crew’s doctor and aspiring naturalist, because, hey, one doesn’t spend four years getting a Biology degree because that think nature is boring. Bettany’s character is meant to provide an occasional critique of the brotherly love the film otherwise embraces wholeheartedly, and it’s necessary. Without, it’d be easy to write the film off as pure man-pandering. Even if it were though, it’d be damn hard-to-resist man-pandering.

With a finale title like “Grand Guignol,” Penny Dreadful was practically going out of its way to raise my expectations. As I’ve said before, the show’s real hook isn’t the macabre horror or gothic aesthetic: it’s the love for theatre. Outside of Slings and Arrows, I really can’t recall another program that centers so much of its story and themes on stage performance. It feels wholly fresh for the medium, and totally strange that it would take until 2014 for a show to wed its dramatic theatricality with actual theatre (which almost certainly means I’m just oblivious to shows that have already tried this…but let’s ignore that, shall we?).

“Grand Guignol” sets a pair of major scenes on its theatre stage that constitute Penny Dreadful’s bread and butter: unbearable yearning and ridiculous action. Caliban saying goodbye to his life behind the proscenium, and the investigation team fighting for their lives below it offers emotion and thrills heightened to supernatural levels befitting the supernatural premise. Penny Dreadful doesn’t really do restraint or subtlety, and I love it for that. Its characters start off as somewhat clichéd archetypes with terrible secrets, but this allows the show to work from the outside in, and the first season has done a really great job of building connections and binding ties between its most important elements…

But, not all of the show’s elements. Or, most of them, really. John Logan has a lot of proven experience in film, but his first foray into TV plays more like a comic book than a show, and it’s hard to tell if he needed more episodes to connect the dots, or less to avoid unnecessary padding. The “twist” with Chandler that’s finally revealed in the finale is a lot of fun to watch, but that’s because we knew it was coming, like, six episodes ago. Hell, it was so heavily telegraphed, I would have gone 50/50 on it all being a red herring. The show’s overarching mythology is still a big mess, and everything involving Dorian Grey amounted to pretty much nothing for the finale (though after watching an early episode of The Rockford Files recently, Rory Kinnear showing up does let me get distracted by how much he looks like a young James Woods).

Not-terribly-long story short: the show is kind of a shambles. But it’s my kind of a shambles, largely because it’s a show about understanding beasts of a flawed nature. I wouldn’t go so far as to say Logan is making a meta-commentary with the season’s final question (“Do you want to be normal?”), but right now I’m glad the TV landscape can offer something as self-assured in its strangeness as Penny Dreadful. Count me in for Season 2.

As 22 Jump Street was wrapping up, I felt like the film had made good on the high praise that’s been heaped on it. The laughs flowed freely throughout, and it’s an action-comedy that actually knows how to shoot its action as more than a joke. Still, apprehension remained: Phil Lord and Christopher Miller had done the impossible by making lightning strike in the unlikeliest of bottles twice. In the wake of the grossly disappointing Anchorman 2, this was a minor miracle, but worry remained: a sequel riffing on the fact that it’s a sequel automatically becomes less funny when its success means there will probably be another entry to come.

Then the closing credits happened, inspiring some of the biggest laughs of the entire film, and assuaging my fears. Turns out, yes, Lord and Miller are even more self-aware than the meta-tastic 22 Jump Street lets on, and clearly, they know they’ve wrung this property out for all it’s worth. It’s hard to imagine Sony and MGM not wanting to team Channing Tatum and Jonah Hill up again, given how profitable the Jump Street franchise has been, but the creative duo responsible for its success behind the camera drops the mic and cuts the power by the time 22 Jump Street is all said and done.

More power to ‘em. 22 Jump Street is lively, inventive, and very often hilarious, but its bag of tricks runs dangerously close to empty. As the film frequently points out, this is largely a retread of 21 Jump Street, with the same relationships and beats either repeated, reversed, or given a fresh coat of paint. The omnipresent, slightly cynical self-aware streak of the whole operation is what elevates the material when the original formula makes itself too noticeable, but that’s a well you can only go to once. For as smart as Lord and Miller (and the writers responsible for the original script) are when it comes to knowing how and when to eat their own tail, it’s ultimately a gimmick. But they know that, which is why, for as satisfying (though maybe just a little less so than the first time) as 22 Jump Street may be, PLEASE, FOR THE LOVE OF GOD, LET’S NOT TEMPT FATE BY DOING ANOTHER ONE.

Having only seen two other Terrance Malick films, The Thin Red Line (which I rather like), and Tree of Life (which I’m still processing), a family member suggesting their interest in watching this sumptuous ’78 historical drama was all the reason I needed to knock Days of Heaven off my to-see list (beefing up my Malick experience tremendously in the process; gotta love directors with small catalogues).

I was awfully surprised to find that the last feature of Malick’s before a two-decade hiatus was only 90 minutes in length. Perhaps the relatively brief runtime is a product of the film’s two-year editing cycle, as paring things down is often about the only power one feels they have once everything is in the can. The brevity is noticeable: Days of Heaven isn’t composed of scenes so much as it is a loosely connected fever dream recollection of a longer, more methodical costume drama.

I appreciated the sparseness of the film’s storytelling as much as I did the jaw-dropping depth of its prairie vistas (most surprising of all: discovering that the endless rolling hills of farmland happen to be in my childhood backyard of Alberta). As is his wont, Malick boils down characters to almost biblical simplicity, using them as spectators to, or props within the wider emotional canvas of his environment. I can see why critics might find the film’s imagery to be letdown by the start/stop narrative, but there’s an intimacy to the world of Days of Heaven that I can’t say I’ve seen in Malick’s other work.

One recommendation: don’t watch the film if you’ve been listening to a lot of Comedy Bang! Bang! lately, or else Linda Manz’s narration is going to do nothing but remind you of Bobby Moynihan as the stabby orphan Fourvel all film.

I consider being poorly-read to be among my greater character flaws, so you should automatically take anything I have to say about literature with a grain of salt. Well, “literature” might be stretching the definition, seeing as I usually only read biographies and paperback beach novels. We’ll wait until I get through the entire works of Shakespeare, and try to sum that up in 10 minutes before the real depths of my illiteracy show themselves.

That being said, The Martian, the story of one astronaut’s struggle to survive while stranded on Mars, is almost certainly one of the worst written books I have ever read. Now, what’s there to unpack within a sentence that harsh and seemingly vitriolic? Well, it doesn’t mean that the book isn’t enjoyable, because it is: Weir has a really entertaining premise that he explores with great excitement and a propulsive sense of plotting. I also don’t want to imply that his chosen background for approaching the material is invalid: Weir’s career in sciences is obvious with every lovingly explained chemical reaction, description of a tech spec, or moment of stakes-raising number-crunching, and it’s because of his passion for science that long passages spent puzzling out answers for high school math/chemistry/biology/physics questions can be very engaging.

My problem with The Martian is that the specificity of its author’s skillset is made abundantly clear by anything that doesn’t feel like it belongs in a textbook. Compelling characters, interesting dialogue, ambient descriptions -all the things that let you invest in a novel, instead of feel free to immediately dispose of it upon completion- are missing from The Martian. The book’s narrative structure relays events in the past tense, so most of the time you’re just being told what the story was. When Weir does break format, it’s jarring, and clearly signals a necessary perspective shift for dramatic effect. It also usually means dealing with the secondary characters, a rabble of paper-thin cutouts that talk like Internet commenters at the hyper-caffeinated pace of Amy Sherman-Palladino characters. The book is wall-to-wall with the smartest people in the world, so hearing them spew nothing but sarcasm makes NASA sound more alien than anything on Mars.

Weir’s understanding of the internal workings of advanced space machinery seems sound, but he doesn’t have a blue print to follow when writing his protagonist. Disguising dated pop culture references as a personality, spending months with the book’s hero becomes a patience-testing chore. Sure, we expect astronauts to be hyper-competent to the point of blandness, but at least someone who’s boring won’t make bad Reddit jokes all day. The Martian is essentially the Apollo 13 of space novels, a uniquely premised and fast-moving exercise in problem solving with a smarmy streak that goes from eye roll-worthy to outright irritating about halfway through.

June 2014: Murder on the Orient Express (1974), Penny Dreadful Episodes 1-7, Louie Season 4 Episodes 1-3, Playing House Through Midseason, Making Movies, Rectify Seasons Premiere, Into the Woods Original Broadway Cast Recording, Fargo Season Finale, Game of Thrones Season Finale, Godzilla (2014), Ida, Edge of Tomorrow, Under the Skin, Mad Men Season 7, Hannibal Season 2

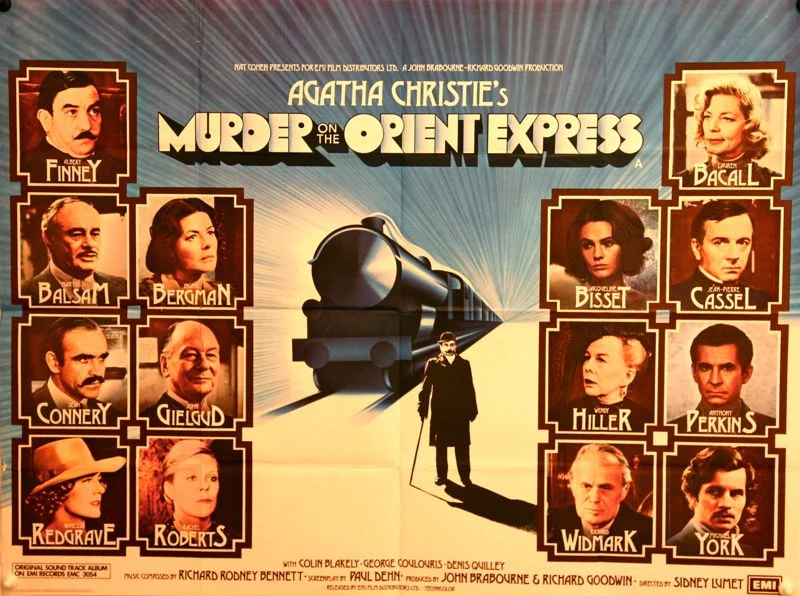

What better way to follow-up Sydney Lumet’s Making Movies (and to celebrate his 90th birthday) than with one of his biggest movies: Murder on the Orient Express, a film so star-studded, you could enjoy a real train ride from Istanbul to Yugoslavia in the time it takes to get through the opening credits. You’ve got Sean Connery, Ingrid Bergman, and Lauren Bacall as just a few of the dozen suspects caught up in a murder mystery on rails, with Albert Finney sussing out the perpetrator as Agatha Christie’s fastidious Hercule Poirot.

It’s the makings of a smash when looking at the talent above line or below, but the reasons why Orient Express doesn’t seem to be one of Lumet’s better remembered works are pretty self-evident. Though packed wall-to-wall with notable actors from both stage and screen (a great anecdote from Making Movies has Lumet recalling how the actors sometimes mumbled during rehearsal due to feeling intimidated by their cross-form counterparts), there’s not a lot of time for development of a cast this large into anything more than a gaggle of suspects (I love Ingrid Bergman [who doesn’t?], but how she got an Oscar for about 5 minutes worth of screen time is the real mystery).

The structure of Christie’s story is confining both physically and narratively, as the rotating compartment door of interrogations gets a little tiring after a while. Finney is terrific in the lead, perhaps because, though I’m ashamed to admit it, this was my first experience with detective Poirot. The story lends itself well to reading or live theatre (I can vividly imagine how a stage working of Poirot’s 30-minute explanation of the crime would go), but as a film experience, Lumet gets trapped along with his guests in very tight spaces, adding an element of claustrophobia to the proceedings, but also a cheap staginess (in contrast, the most memorable shots are long tracking sequences that highlight the massive expanse and expense of the Orient Express itself).

The film has to frontload its exposition directly with a newspaper montage that makes for a dry follow-up to the extensive credits, but the final piece, a headline about a dead little girl that glows red like a hot brand, makes for an indelible image. Looking online makes it appear that the film was originally screened in black and white, so I have to wonder if my issues with the mis-en-scene would have been less severe had my viewing not been in colour. Regardless, the actorly wattage of Murder on the Orient Express will carry you through to its surprising and surprisingly morally ambiguous ending, and makes me think I should be spending more time with both Lumet and Mr. Poirot as soon as I can.

Pilot

The good buzz I’ve heard on Showtime’s latest seems to be warranted, at least through the first hour. Figures that a few clicks over you’ll find me saying there’s nothing quite like Hannibal on TV, and then what should appear but a cable series that shares a lot of its basic DNA: both are a reimagining of a well-known macabre property that oozes mood and viscera, but one that can fit just fine within the trappings of a procedural.

The adaptor in this case would be John Logan of Skyfall fame, and the overlap here makes sense beyond just the inclusion of a former Bond and Bond girl (and, I’m pretty sure, use of J. M. W. paintings). Logan’s Skyfall was about cracking open the pulpy but ironclad outer shell of a cultural icon to see what made him tick. The movie could only go so far within the timeframe of 2 hours with a character as controlled as Bond, but Penny Dreadful is already showing immense promise in terms of how it might take characters of Victorian literature, and make them into television versions of real people.

The pilot is really a lot of fun, in part because it hues strongly to the conventions of a team-up serial, the kind that The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen did well when using these characters in comic form, only to be butchered in movie form with a different Bond at the helm. It established roles for the all the characters as part of a potential working group, and it’s easy to see how the show could make for a modern (read: bloody, scary, naked-y and swear-y) take on Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s monster of the week format.

But the pilot works just as much for how it subverts your expectations, in particular with the characters. The darkness dominating the pilot isn’t just magic and superstition, it’s existential; when two characters are talking around this other world of darkness they’ve peered into, they’re as much talking about actual supernatural evil as they are the missing piece in their lives that’s pushing them into the frightening unknown willingly. Though it plays coy with the deep dark secrets the leads are being driven by, that they have that drive is really quite impressive. The Josh Hartnett character, a cynical American actor and war vet, could very easily have been the main fish-out-of-water perspective for this gothic setting. The handful of characters who seem likely to make up the core cast all display an obsessive thirst for something by the end of the hour, so I’ll definitely be tuning in for more.

Episode 2: Séance

“Séance” is a really great bait and hook of a second outing for Penny Dreadful, which is quickly rising on my “God, I hope this is as good as it could be” list. The first half or so is full of the usual kinds of concessions a show will make to get the attention of viewers who didn’t tune into the premiere based solely on the premise, and therefore might need a little more enticing. The opening half abandons the dread of the pilot for a lighter touch, thanks to a new character played by Billie Piper, who says she’s from Ireland, but whose accent travels all across the European continent in a given sentence. I was unfortunately captivated by Piper’s affections so I spent a good long while wrestling with them instead of hearing any of the banter she was trading with Josh Harenet. Later, a sex scene between Piper’s character and the show’s tweenage heartthrob of a Dorian Grey made the episode’s plays to the cheap seats seem even more apparent.

But then the episode has the titular séance, and all bets are off. Before saying anything else, it should be emphasized how much of the show’s strengths and potential are tied to Eva Green’s performance style. She doesn’t so much go for broke and seem completely oblivious to the idea of limits; there’s no vanity to her embodiment of the character, so she’s freed herself to inhabit the role fully, regardless of how out there things might get.

The episode crosses back over into its weird and deliriously fun fringe territory when Green’s character becomes possessed by a spirit, and goes through the usual stages of being a possessee. Contortions, a 2-pack-a-day Clint Eastwood growl, and a desire to taunt those around you is the devil’s playbook as established by every exorcism movie ever, but because we’ve established Vanessa as a character, and she’s being plaid by Green, the scene puts to shame many cinematic attempts at aping The Exorcist.

Because we’ve started to establish a familiarity with these characters, the trauma brought about by and implied during the exorcism has weight; we’ll carry on the details we think we learn about Sir Malcolm with us going forward, and that gives the scene its emotional heft. What we do piece together about Malcolm’s tragic backstory hints at something very wrong in his relationship with his daughter, and his feelings on his son, and by letting Green tear like a hurricane through the scene, it makes Dalton’s work that much more powerful.

To sidetrack: the episode’s ending revelation is definitely the kind of WTF-#PennyDreadful-GIF-Tumblr bait that the show could have capitalized on if it was airing on a network (and had, oh I don’t know, about 10 million more viewers). It’s a bold move ripe with potential. Perhaps because I thought where the plot was going originally had many interesting avenues available already, that we won’t see them (at least for now) means that the last-second reversal earned its dramatic punch. Good stuff.

Episode 3: Resurrection

Arguably the biggest reason reboots/reimaginings work is because established fiction has built-in hooks for the audience that an entirely fresh property doesn’t come equipped with. We’re in the jazz-era of TV and film, where the core of western fiction has been so deeply established that all there is to do now is riff on that core using the instrumentation everyone is already familiar with.

To that end, I realize Penny Dreadful isn’t a revolutionary show, or even groundbreaking, but it is rejiggering elements of story and character into combinations I wouldn’t expect, and therefore, I’m feeling the same dopamine kick of surprise that you get when something legitimately original and innovative comes along. Episode three does an impressive job of humanizing Frankenstein’s original monster, who loomed heavily as a threat in the last episode’s nasty cliffhanger. They do it even better than their back-fill on Frankenstein himself this week, seeing as the pathways in my brain stimulated by characters with unresolved mother issues are all-but attenuated at this point.

But creating a literally theatrical villain by giving him a home in the theatre? I’ve got to say, I love that idea. Again, it’s not half so clever a story as my brain thought it was at first brush, but Logan uses the component to unify and give different perspectives on the show’s established themes. Theatre, as the primary non-literary form of entertainment of the era, was where an audience would go to escape their problems. Extrapolate that to its furthest conclusion, and even at a show like Sweeny Todd (which Logan worked on the recent movie adaptation of), the viewer is there so they can forget about death.

And it’s in the theatre that those who have cheated death live on, in the form of characters and playwrights that endure for hundreds of years. Of course, the show’s theme of change also works here too; just as the industrial revolution has replaced so many workers with machines, The Creature’s mentor must lament that the days of Shakespeare have given way to Ibsen. Everyone on this show is looking for something solid to cling to as they grapple with what they are afraid of, and so by hour’s end, The Creature’s pained request for a companion hits like it needs to. It goes to show just how good Penny Dreadful is getting at making us sympathize with the monsters.

Episode 4: Demimonde

I like Josh Hartnett in this show. As one of the more frequent weak links being pointed out by others I see talking about the show, I think what Hartnett is doing with his character is really engaging. Yes, he looks like he came out of the same genetic tube that spawned Ethan Hawke, just with a lower incubation dose of raw talent, but the show has played into his strengths as a hunky dope really well, in particular because of how it’s handling Ethan Chandler as a character.

There’s a really smart little bit from the pilot where after Chandler pulls a lady from his audience for some rather unfulfilling backstagecoach sex, he goes through the usual theatrics of a guy looking to drop the one-night stand like deadweight. Normally, we’re supposed to be smitten with the cad’s feigned heartbreak, and the gal he’s just pulled one over on is meant to either buy the illusion, or just generally look like a dimwit for expecting something more out of the guy.

But the show flipped that with just a line, as the random women responds to his bullshit toast to the memory of their tryst with a simple question: “won’t you want to know my name at least?” she asks, with a playful sarcasm that indicates she knew going in that more than likely, both were just in this for a quick lay. Giving the woman the last word not only makes her seem like an actual person instead of just a rube bedpost notch to elevate how cool our hero is, but it also lets us get a moment with Chandler to really hammer home that yes, he’s somewhat ashamed of his actions, and all the moreso because they’re not filling the emptiness in him.

With that, I think the show established a baseline awareness of its sexual politics that it’s been following into interesting territory. Everything between Hartnett and Piper’s character was pretty rough tonight, as Mrs. Croft is kinda the worst even without my accent issues. Like episode 2, “Demimonde” really snaps into place when centered around a piece of theatre, here an actual play instead of a séance. Art as an expression of inner anguish has been a big theme for the show thus far, and every one of the main characters is putting on some kind of a performance.

For Chandler, a B-movie play version of his worst fears don’t frighten him, as he’s come to love the theatrics in both his profession and personality. An underground rat-hunting ring contains the same savagery as the play, but doesn’t dress it up. Chandler loses his cool because he needs that layer of fiction that makes up his cowboy persona to armor himself against the world’s nature and his own. I think we could be getting a really neat look at the stock masculine cowboy role Hartnett’s supposed to fill, and the ending for this week gives a strong indication that traditional gender norms aren’t Penny Dreadful’s interest.

Episode 5: Closer than Sisters

The big challenge shows face when trying to build a cast out of characters who don’t already have a history together is that you have to get around to establishing their individual backstories at some point. Something like Game of Thrones involves so much shared history that you can usually get away with info-dumping using monologues and storytelling, but not every show is so lucky. Usually, the flashback is the way to go, and some programs treat the narrative construct as a key part of their DNA, Lost being one of the more famous examples, and Orange is the New Black being a more current one.

Penny Dreadful’s appeal stems from two specific sources that don’t jibe particularly well with flashbacks: the diverse cast of characters, and the mystery surrounding them that’s thick enough to insulate a house. “Closer Than Sisters” bumps up against both of these constraints in spending the entire our letting us in on the history of its most intriguing character, Vanessa, the problem being that info is often the death of intrigue. On paper (which the entire episode is, given the conceit that we’re finding this all out in the form of a letter), what the hour has going for is that it’s pretty much the Eva Green Show once the moppet versions of Vanessa, Mina and Peter’s youth take a hike (that’s not a slam on the kid actors, who are all quite good. But, come on, the show pretty much pulsates when Green’s on screen).

Great as Green’s performance still is, it’s responsible for elevating some tired material. Infidelity at an English manor makes for a slow buildup to the show’s particular breed of horror, but a trip to the asylum was not my preferred way of getting back into the gothic groove. I can see the appeal Logan might find in the setting, as the torture Vanessa suffers at the hands of her caretakers is more frightening than a thousand red-eyed ghouls, and it is based on the actual mental health care standards of the day, only amplifying the terror. And just speaking personally, psychiatric horror has always been a horror pressure point for me, but what left me more squeamish was the need to fill in Vanessa’s backstory with physical trauma and abuse, which can be a lazy shortcut to audience sympathy. All the dudes on the show are dealing with angsty man-pain and guilt, so surely Vanessa’s angsty woman-pain and guilt were already enough without the ice baths and head-drilling, right?

We’ll see. I’m hoping the show starts pulling its threads together for the last few hours, as it feels like enough of the players have been sufficiently setup that we can start letting them play together again.

Episode 6: What Death Can Bind

CHICANERY! Much as that really is the vital piece of dialogue from this week’s episode for understanding the theatrical charms of Penny Dreadful, the actual thesis statement comes the scene after. “To be alien? To be disenfranchised from those around you? Is that not a dreadful curse?” As delivered by Eva Green as just the opening volley in a game of theme tennis with Reeve Carney’s Dorian Gray, it’s a little overripe like the entirety of the scene (again, theatrics being the show’s most endearing quality), but it does crystalize the real fear behind Penny Dreadful: being alone.

“What Death Can Join Together” is a nice congealing of the show’s strengths after the last couple episodes split them apart, and the result is probably the most consistent hour of the show since the pilot. Though the hunting party for the action set piece was smaller than usual, with Vanessa off on a date, and Frankenstein brushing up on his vampire lore, the episode connected all the dots marvelously by showing the characters in various stages of relationships, and the differing ways they try to hold onto them.

For Chandler and Croft, a mental picture will have to suffice, as their romance seems terminal. The degree to which they seem to love one another is hard to buy, as not only have I not really liked the Croft character, but we’ve barely gotten to know her, let alone Chandler. Still, the haste of their relationship is perhaps what fuels the passion, which is valid enough reason. As a counterpoint, the longest coupling was presumably between Dr. Van Helsing and his wife, his crystal clear memory of meeting her erased after we find out how they finally parted.

Vanessa and Dorian, class acts that they are, go with paintings and photographs to capture their moment together, which lets the show add on more and more nods to Gray’s literary origin, that at this point it might be a fakeout. The show is keeping the identity of its monsters so close to its vest that the most obvious answers seem to obvious (chicanery?! We’ll find out). It’s The Creature who’s most desperate to have something to hold onto, as he’d rather have a partner who lives forever than risk being left alone again.

It’s an old saw, but the desire to connect is the overriding drive behind all these characters, as it was for many of their literary counterparts. The opening credits, which I’ve grown to really love, offer the best representation of the show’s central interest. The first half is all mood and dread, a drumroll to the horror show you’re meant to expect. But the second tells a different story, and rather than just representing the characters with sinister symbols, we get to see in profile looking as human as they might ever be- distant, but reaching out for something to hold onto (save for Danny Sapani as Sembene, who just looks kinda bored; can’t blame him, as he’s had very little to do so far). They may be monsters, but the contours of a snake can be beautiful when you look closely enough, and even a bat may want to take flight in the sun from time to time. Another two hours as focused as this one, and Penny Dreadful should end its first season in fine fashion.

Episode 7: Possession

“Possession” is more or less everything one could really ask for out of Penny Dreadful, and represents the show operating at (what’s currently) its upper limit. It had all the basic ingredients of the series’ appeal at its disposal, and threw them all into the pressure cooker that is Sir Malcolm’s mansion. Cook time: one month. The result is an hour overflowing with atmosphere, shady backstories, and some of the biggest flashes yet of pure horror.

It’s tempting to just call it “The “Exorcist episode,” but the majority of “Possession” is about everything that happens on the way to getting a priest. Rather than focusing on solving Vanessa’s possession as some sort of immediate end goal, Penny Dreadful settles in for the long haul, in the process establishing the perfect excuse to get all its characters under one roof for an extended stretch of time. It’s an inspired structural choice, as many seasons of television take place over a shorter period of time than “Possession” compresses into an hour.

But you feel the length, which is vitally important to understanding the show’s approach to these well-worn character types, and its own themes. While the flood of spiders and the increasing layers of flop sweat on Eva Green (whose continued excellence here would require well more than 10 minutes to sum up, so I won’t even attempt to) represent the show at its most theatrical -and at its most obsessed with theatricality as a means of connection-, the broader themes are what’s being pulled together by Penny Dreadful tonight.

The actual mythology at play reads to me like a big mush of Judeo-Christian devilry with some added occultism for flavor, and that’s all serviceable. Even though the literal devil is threatening the end of the world, the most captivating conversations are happening between the other characters as the days stretch on into weeks, and everyone starts getting exhausted and strung out (that goes double for Frankenstein). As supporting Vanessa takes its toll, the personas and costumes the characters protect themselves with start to fall away, tempting everyone to start speaking as openly and honestly as possible.

Penny Dreadful’s period setting allows Logan to draw on past historical traumas and present them as being part of what these characters hide with their outsized personalities. Just as The Wolfman, Frankenstein’s monster, and Dracula can become blown-up metaphors for national anxiety, the human versions of their alter-egos are shaped by regret and fear on a scale that’s greater than just personal. Over long nights of staring literal evil in the face with Vanessa, the American colonial past of Chandler and the British colonial past of Sir Malcolm come to the foreground with force; these aren’t the defining motivators behind these characters, but their personal identities are unmistakably marked by their national ones.

It’s such skeletons in everyone’s closet that let the show’s most powerful demons, shame and regret, come out to play. Frankenstein, despite being the smartest guy in the mansion, diagnoses Vanessa like any ignorant doctor might at the time: blame it on suspicions of sexual trauma. In essence, he’s willing to chalk up all the crazy shit he’s just seen to Vanessa having lady parts, which speaks to his ignorance as an individual, and a student of a field still ignorant about many things at the time.

The clever bit is that Logan flips Frankie’s expectations even further a scene later, when Vanessa uses her knowledge of Chandler sleeping with Dorian Grey to try and castrate the swaggering cowboy. Sir Malcolm is a hard man whose experience in Africa is so wrapped up in the death of his son that he doesn’t seem to care how his other actions there affected the continent. He’s a callus, but weak man, a father trying to hold onto his daughter by risking her best friend. Chandler, the American with New Empire idealism, wants to believe he can do better, but his own shame for the things he’s done and seen makes him prey to someone like Dorian Grey, or the devil inside Vanessa wanting to further shame him for showing vulnerability.

On a plot level, there were things about “Possession” that bothered me (I think we needed to spend more time seeing Vanessa’s perspective as she grappled with the demon’s influence, and the seemingly literal deus ex machina was a headscratcher), but the mythology stuff is all just bells and whistles ultimately. Penny Dreadful knows that entertainment can be at its most powerful when going for spectacle, but the real heart of theatre just comes from having one person willing to share something, especially a secret, with another person.

Episode 8: Grand Guignol

With a finale title like “Grand Guignol,” Penny Dreadful was practically going out of its way to raise my expectations. As I’ve said before, the show’s real hook isn’t the macabre horror or gothic aesthetic: it’s the love for theatre. Outside of Slings and Arrows, I really can’t recall another program that centers so much of its story and themes on stage performance. It feels wholly fresh for the medium, and totally strange that it would take until 2014 for a show to wed its dramatic theatricality with actual theatre (which almost certainly means I’m just oblivious to shows that have already tried this…but let’s ignore that, shall we?).

“Grand Guignol” sets a pair of major scenes on its theatre stage that constitute Penny Dreadful’s bread and butter: unbearable yearning and ridiculous action. Caliban saying goodbye to his life behind the proscenium, and the investigation team fighting for their lives below it offers emotion and thrills heightened to supernatural levels befitting the supernatural premise. Penny Dreadful doesn’t really do restraint or subtlety, and I love it for that. Its characters start off as somewhat clichéd archetypes with terrible secrets, but this allows the show to work from the outside in, and the first season has done a really great job of building connections and binding ties between its most important elements…

But, not all of the show’s elements. Or, most of them, really. John Logan has a lot of proven experience in film, but his first foray into TV plays more like a comic book than a show, and it’s hard to tell if he needed more episodes to connect the dots, or less to avoid unnecessary padding. The “twist” with Chandler that’s finally revealed in the finale is a lot of fun to watch, but that’s because we knew it was coming, like, six episodes ago. Hell, it was so heavily telegraphed, I would have gone 50/50 on it all being a red herring. The show’s overarching mythology is still a big mess, and everything involving Dorian Grey amounted to pretty much nothing for the finale (though after watching an early episode of The Rockford Files recently, Rory Kinnear showing up does let me get distracted by how much he looks like a young James Woods).

Not-terribly-long story short: the show is kind of a shambles. But it’s my kind of a shambles, largely because it’s a show about understanding beasts of a flawed nature. I wouldn’t go so far as to say Logan is making a meta-commentary with the season’s final question (“Do you want to be normal?”), but right now I’m glad the TV landscape can offer something as self-assured in its strangeness as Penny Dreadful. Count me in for Season 2.

Episode 1: Back

Hey, Louie’s back! Or was, anyway: the fourth season wrapped up last week. But seeing as I only just caught the premiere…hey, Louie’s back! After taking 2013 to kick up his heels for a bit, Louis C.K., who’s become pretty much the biggest thing in comedy over the last few years, has a new set of short films masquerading as TV to share with the world.

Like a lot of TV-loving people, Louie’s been a constant source of surprise and joy since it started airing, as much of its unique flavor is owed to C.K.’s complete control over just about every aspect of the show. This has allowed him to cover subject matter that’s controversial, personal, disgusting, insightful, or any combination therein, and do it all while playing with form in ways no other show can.

Season 4 opens with the show at its most oneiric, but considering David Lynch was part of a multi-episode arc last season, having Louie engage in a strange conversation with another comedian while everyone else in the café is texting on their phones really isn’t outside of the show’s version of reality. The opening bit about overly loud trash collectors was a great reintroduction to the show, mixing observational humor and ridiculous physical comedy with a nice reminder that the show is finally out of its long slumber.

“Back” plays up that sense of excitement that Louie has returned, as it’s something of a greatest hits showcase for some of the series’ previous highlights. Louie’s daughters are back for a couple of very endearing scenes that breakup the surrealism, and he ropes a bunch of his comedian friends back in for another poker game, which is really just an excuse to here funny people riff about masturbation and sex toys. That the rest of the episode can then take all the dirty talk and build it out into a anecdote around Louie getting older is just another example of the show’s ability to have seemingly stream-of-conscious ideas pulled together into a single story.

I’ve felt the tremors from a greater Internet divide in the Louie community as it has aired over the last couple months, so it’ll be interesting to see how the rest of Season 4 develops. I’ve been wondering for a while if peak C.K. had been reached, and if success would not so much go to his head, as it might blind viewers to when Louie does make a mistake. We’ll find out.

Episode 2 "Model"/Episode 3 "So did the Fat Lady"

Yup, I think I’ve got a bit of an idea how this season of Louie could end up being divisive. FX’s decision to air the fourth season of the show in double installments probably caused plenty of problems for viewers watching live, as there appear to be more multi-part arcs this year. Watching episode 2 and 3 back-to-back, I was getting the back half of week one, and the first of week two, and they represent such a drastic difference in quality, I’m not sure I’d have taken the viewing well with a week in between.

“Model” is Louie devoting a whole episode to self-loathing navel gazing , something the show has dealt with plenty of times before. The setup is funny, as Jerry Seinfeld is present to play himself as a kind of anti-C.K.: rich, respected, and together, but something of a dick, which Seinfeld plays well. But there’s only so much of C.K. in “universal piñata” mode I can follow before it seems like a one-note gag, despite dressing it up with class implications. It’s a purely comedic episode in which the joke is how increasingly discomforting the situation becomes for Louie, but it doesn’t have the follow-through other C.K. shaggy dog stories have had.

Now, try washing that out with “So Did the Fat Lady,” and you remember what C.K. can do when playing with uncomfortable truths instead of just awkwardness. Part of the contrast is that “So Did the Fat Lady” is an episode with happiness in it; even Louie’s self-loathing bang-bang ritual (in which he and his brother eat a meal at one restaurant, followed immediately by another meal somewhere else) has joy to it. The source is mainly Sarah Baker, who pursues a date with Louie with all the charm and warmth he himself lacks when he’s not onstage.

The chemistry the two have together as they walk and talk around New York is meant to make Louie look like a yutz for putting her off for the first half of the episode, but there’s more to it than that. After a seemingly insignificant comment, Baker has an absolutely inspired monologue that dregs up all the unspoken subtext of their relationship up to this point, and it’d be painful to watch if it wasn’t so specifically, pointedly true. The episode then, in contrast to “Model”, finds a way back to joking about what Louie’s experienced in a why that makes the punchline feel earned, and I’m in love with the show again. Things could still get plenty bumpy through the rest of the season, but “So Did the Fat Lady” is already a frontrunner for its highpoint.

Pilot:

Well, this could be fun. The ceiling for Playing House seems pretty low based solely on its premise, which sees wayward best friends reunite in their hometown after the job-driven half of the pair loses said job, and the very pregnant other half kicks her cheating husband to the curb. It’s a pretty rote setup, and the weaknesses of “Pilot” usually spring from just trying to barrel through setting it up.

What Playing House does have going for it is a really terrific cast, led by Jessica St. Clair and Lennon Parham. I mostly know the two from their work on the podcast Comedy Bang! Bang! (which the pilot borrows some of their material from). Even in just an audio format, it’s clear that St. Clair and Parham are an amazing match for one another. There’s a really great balance the two have in just about every regard, from delivery, to physicality, to voice pitch. As such, having St. Clair’s excitable Emma move in with the drier Maggie has the basic dichotomy of personalities most comedies demand, but the two are at their best when riffing together, which is often.

That’s what I’m hoping Playing House will develop into before too long: a really great hangout show. It’s also got Keegan Michael Key of Key & Peele fame, and the scene-stealing Zach Woods from Silicon Valley, so St. Clair and Parham aren’t rolling in here without talented backup. But it’s the central friendship between Emma and Maggie, a rare thing to base a show on, rarer still if it’s female-female, that could enable the show to be a funny, empathetic treat. I chuckled a fair bit through “Pilot” (St. Clair saying “butt” is Platonic funny), but the exchange late in the episode between the leads that drives home the sometimes-unflattering depth of their friendship really sold me on the show having strong emotional potential. The episode then proceeds to oversell the moment a little bit, but that’s all part of the growing process for a freshman show.

Midseason:

Playing House is perfectly pleasant television, the kind that can get away with things that might irk me on other programs. The sets look like sets, everything is over-lit, and the characters live in palatial dollhouses despite none of them having jobs. These are the sorts of things that can make your average sitcom feel hacky when going for cheap laughs, or obnoxious when trying to maintain an air of self-importance about itself (think How I Met Your Mother’s byzantine plotting around fulfilling its title obligation).

Playing House thankfully doesn’t try to aim beyond its means, or for the cheap seats. It recognizes the storytelling limitations and strengths of being focused mainly on the friendship between Emma and Maggie. The sheer warmth and conviviality of the central duo allows the show to write around incredibly small plot stakes that nonetheless carry strong emotional ties. The fifth episode centers around Maggie trying to redeem a bungled high school passion at a reunion for her marching band, which is a goofy premise in service of showing these characters as having realistic feelings about missed opportunities and overlong regrets.

Parham and St. Clair are strongly matched foils for one another because their friendship has the spark and fuel that makes energetic conflict come easy. This isn’t a dramatic show, but it doesn’t position itself as outright airless either, and Playing House tries to treat even its most out-there characters as humanely as possible. Also helping matters is that so many of those one-shot characters are played by really talented comedic actors, including Review’s Andy Daly, Jane Kaczmarek, and the increasingly ubiquitous Jason Mantzoukas. As hoped, Playing House at its halfway point is already a pretty solid hangout show. It’s maybe not the kind that has you doubled over laughing with every episode, but it’s got a skip in its step and a thick rolodex of funny people to bring by every once in while, so it’s hard to find Playing House as anything less than amiable.

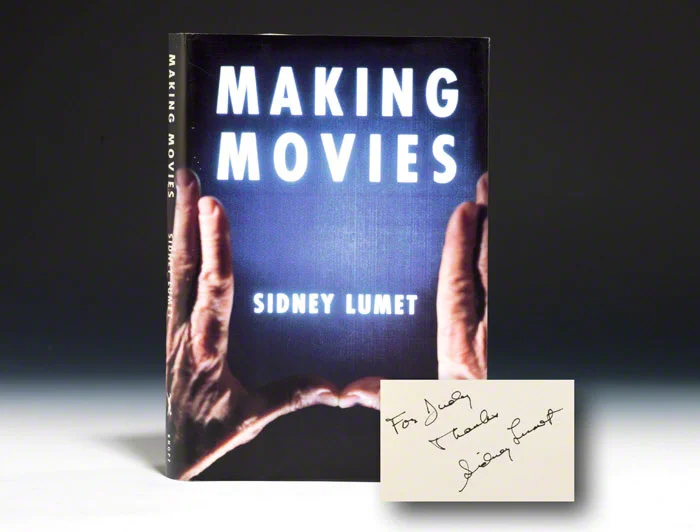

Hey, it’s one of them paper thingies. Like a script, but without stage directions, and written entirely in prose.

Seeing as Making Movies is considered one of the holy texts of the film world (and I had it on loan temporarily), I managed to burn through this over a couple sittings. I had originally been holding off until I had seen more of Lumet’s work (Dog Day Afternoon and 12 Angry Men being the only two I recall watching with any clarity), but turns out that shouldn’t be a barrier to entry. True to its reputation, the value of Making Movies is pretty universal to any film fan, as it offers an insider’s perspective on the day-in, day-out, honest-to-god work that’s required to make movies.

Or, was, anyway. Released in ’95, a fair few years removed from Lumet’s best work, the industry has changed quite a bit since. The word “digital” pops up occasionally like someone in Game of Thrones hearing rumors of a dragon overseas, so what of Lumet’s experience still practically applies to today’s Hollywood is a bit of a mystery. Despite opening the book by stating it will not be a laundry-airing tell-all, Lumet is just as engaged talking about stars and industry people as he is craft. He sounds pained to ever say a bad word about anyone, even when not naming them, and his constant stream of praise, be it for actors like Pacino, or tireless studio bigwigs like Margaret Booth, is endearing.

Making Movies is a vital text for film lovers not just for how effectively Lumet takes you through every stage of the filmmaking process -helpfully defining jargon where necessary and using his own films as examples regularly-, but for how clearly it makes you understand the effort and passion required to make even bad movies. Audiences, myself included, often take for granted the sheer number of hands and hours that go into developing even the most minor details of a production (following a difficult and limited location shoot, Lumet describing his lighting coordinator discovering a bad setup while watching rushes for The Wiz is almost heartbreaking).

Perhaps it’s that digital beast that’s made it easier for us to slip into cynicism about moviemaking more readily, seeing as everything these days increasingly feels like it was made on a computer. There’s romanticism for “the good old days” about the book, some problematic elements of which Lumet himself readily acknowledges. His superlatives are never more exhausted than when talking about Spielberg, whose Schindler’s List is frequently cited as the best work to come out of the (then) modern era. In that respect, I’d like to see Spielberg write his own Making Movies at some point, and have him share his experience with modern Hollywood the way Lumet has for middle age Hollywood. Overall, Making Movies makes for a brief but enlightening tour behind the scenes as led by one of the greats of a bygone era.

This is probably the worst show to write about using this arbitrary time limit I’ve given for myself. Hey guys, there’s this really amazing show on Sundance that’s meditative and reflective, and I’m going to compress the experience of watching it into a writeup that takes less time than your average drive-thru trip. It’s a disservice to the show to try and be so off-the-cuff about it, but it’s not like I’ve had better luck talking about it after deliberating greatly on its worldview and merits. The little blurb I wrote about it for last year’s Top 10 Shows list was the hardest to generate, as the show is a bit like that physics principle about interacting with an event changing its properties.

Now I’m at the risk of hyperbolizing it too much, so maybe just read Matt Zoller Seitz’s review for the Season 2 premiere over here to get what is is that makes the show so appealing, and hard to write about. As for the premiere: I thought it was a somewhat weak installment for the show, which is typical of many follow-ups to the climactic finales of the year previous. The fallout from Daniel’s assault (that’s as big as the show goes: a guy gets beaten up, and it feels like the end of the world) gives us plenty of time to get reacquainted with the people of Polly, Georgia, and play a bit of catchup as to where they are emotionally.

It plays a bit like busywork at times, which is unlike the show. Much as I was happy to see Amantha, Tawney, and even Ted Jr. again, there’s almost a surfeit of plot (by the show’s standards) to get through in order to set things up for the next 9 episodes. Of the plots, Sherriff Daggett investigating Daniel’s attack is the most engaging so far, as it’s the most connected to the characters we care about. For now, I’d rather the senator, Bobby Dean and the other good ol’ boys stay in the background, and the focus remain on the Holden family and Daniel.

When the show does that, as the premiere does in the opening and closing scenes, the show becomes hard to describe as anything other than transcendental. Rectify is a show that grapples with faith in ways that are unlike anything else on TV. Even shows I love, like Hannibal, use existential questions as a means of heightening the drama behind the plot. Here, the spectrum of beliefs these characters provide is organically drawn from everyday ways of in which people find themselves asking the big questions. Daniel’s dreamlike-state for the premiere lets Rectify foreground its struggles with the unknown more than usual, and it’s not cheating: the show has earned the weight of its inquiries, and both the pace and method in which it wants to explore them. The six episodes we got last year would have been enough to make Rectify something special, but it’s my hope that series-creator Ray McKinnon was just getting started.

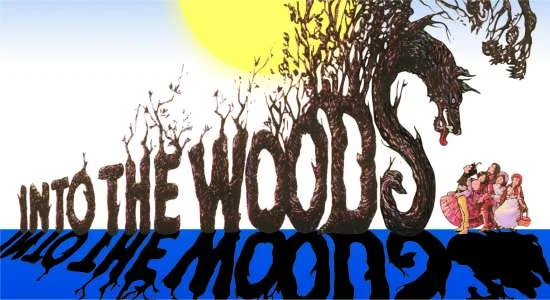

Between reviewing Jersey Boys and some recent industry news, I figured it was about time I revisit one of the first musicals I have memory of ever seeing: Into the Woods. One half of my family is big into Sondheim, and while I generally prefer my song ‘n stage experiences on the comedic side of things (The Producers being my favorite), I’ve always respected the likes of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street and Into the Woods for just how dark they are compared to most Broadway fare.

Of course I was basing this opinion of Into the Woods solely on very loose memory, as I haven’t seen or heard it in probably more than a decade and a half. But when it recently got out that Disney was, well, Disney-fying (read: bowdlerizing) the source material for the film adaptation coming later this year, I figured it was time for a revisit. And, yes, now I pretty clearly remember the parts of Into The Woods that aren’t quite on-brand for the House of Mouse: psychological trauma, infidelity, murder –basically, the entire second act.

But that’s the appeal of Into the Woods: the idea of taking children’s stories and seeing what happens after Happily Ever After. It’s an often-grisly play in terms of the fates that befall the characters (though not without it’s own sinister whimsy; the fate of the narrator is one particular twist I’ve never forgotten), but the thesis running through it is actually pretty optimistic. It’s the rare fable, or musical for that matter, that advocates for making the best of a bad situation. You can take that as being cynical, but I think that’s what makes the show appeal to adults and families: it’s about recognizing that the morals of most fairy tales are really just a way of preparing you for a world of compromise.

The Broadway cast recording that’s on Netflix was filmed in 1990, and it makes for an interesting living room-theatre experience. You can find in my review plenty of griping about how Jersey Boys fails as a movie when you try to make it one, and the cast recording of Into the Woods provides an interesting contrast in how one can go about filming an actual stage performance. I think I would have preferred a static camera placement so that the feeling of being in the audience would be more authentic (though mixing the shot angles up does highlight little details you might miss), but the camera work is effective overall, and invites you into the experience in a different way than seeing it live would.

As for the film version, the changes I’ve read about sound kinda antithetical to the whole point of the play. The fact that Sondheim has signed off on the remixing, ironically, proves he knows the moral of his story better than anyone: sometimes, you gotta settle. It’s a shame, because the cast list is pretty strong (at least as actors; who among them can sing other than Anna Kendrick I don’t know), and Emily Blunt is playing my favorite character from the show, so definite bonus points there.

It’s probably for the best that there’s been a flurry of thinkpieces today about the Fargo finale which address my main issue with it, namely that it sidelines the series’ best character. Willa Paskin over at Slate has an interesting look at whether or not the show subverted or embraced the White Male Anti-Hero tropes I thought it was playing with when it premiered, while James Poniewozik over at Time has a read on who the real heroes worth rooting for on the show were.

There’s been a lot of good writing and thinking that’s come out of Fargo, which just makes it even more difficult to believe that the whole thing wasn’t a giant disaster. Beyond the issue of trying to stretch out and remold 98 of the best minutes the Coen brothers ever filmed, the show had interests and a tone that have become wearying; emasculated men lashing out at those around them, impossible-to-touch evil masterminds that always get away, a lot of poe-faced philosophy about man as an animal, good and evil, the heart of darkness blah blah blah.

The obvious point of comparison Fargo has had in this television season has been True Detective, and thanks to last night’s finale, I can say pretty definitively I prefer the former to the latter. True Detective masked a well told and trod procedural in the yellow cloak of an eldritch horror story, before deciding it was really just about two bros dealing with their man-pain. Fargo wove in biblical and fable-like elements much the same way, but at least had a sense of humor about it (more than two characters worth caring about).

These are both bleak shows in their ways, but only one justified its rally for sanity and goodness at the end. Fargo similarly left its fair share of unanswered questions and loose threads, but the ending was true to all that had come before it. I’m not entirely sure of whether FX will go through with a season two, or how they could; maybe we should just thank our lucky stars one season turned out to be such a surprise success. But if there is more to this story and theme that Noah Hawley feels needs telling, then so be it.

I’m not really sure how to feel about Game of Thrones anymore. I really liked the premiere episode for this season, for a lot of reasons that had nothing to do with getting to see it early thanks to a screener. It was good enough to watch on a muddy, watermarked DVD 3 times, and every time I watched it I felt like new depths to the story and the craft were revealing themselves. But Season 4 closing out on two weeks of spectacle and climax has dulled the remaining excitement I had for the show that had been slowly being whittled away over the course of the season.

Before this gets too negative: I still really like the show for a lot of reasons. The production values and designs are some of the most visually engaging I’ve ever seen, TV or otherwise. The scope is consistently awe-inspiring, and that the show can juggle all its various balls as well as it does is a real feat. But it’s gotten to a point where I recognize that what the show wants to be good at, and what I want it to be good at, are separate things entirely.

One of the big climactic scenes from last night’s finale had two sets of characters that never overlap in the books crossing paths with one another. The change makes sense: it adds weight to both of the show’s versions of these threads, and the motivations behind what happens during the meeting are sound. What we get is a fantastically choreographed and brutal fight scene, which is great and exciting on its own terms. But that’s not really what I look for from this property; while the show was teasing us with hands on hilts, just waiting to draw blood, all I wanted to shout at the screen was “Put the weapons down and have a conversation, dummies! You’re all too interesting to just be used as grist on the murder mill!”

Game of Thrones is about as good an adaptation of George R. R. Martin’s books as could ever reasonably be expected, but its malignant case of adaptation-itis is only getting worse with each season. Scenes that work within the ephemera of Martin’s text fall flat when actually filmed, as is the case of Bran and the episode’s little Harryhausen tribute. As has been said elsewhere, the show is often at its best during monologues, particularly when it’s one character telling another a story. I’d be lying if I said last week’s free-for-all at The Wall didn’t have me making noises unbecoming of a person my size, age, or gender, but the thrill was fleeting. The characters, their challenges, and the choices they have to make: that’s what makes Game of Thrones tick.